Had the Football Association opted for Eddie Howe as manager, in the way that many wanted due to his nationality, there would have been an awkward truth. The Newcastle United manager isn’t strictly a product of the English system. Howe did his coaching badges with the Irish Football Association.

It is an issue that has come up a lot this week, as the FA opted for a product of the German system, in Thomas Tuchel. And how couldn’t they? As one senior football figure observed on seeing the job description, the requirement of trophies essentially ruled out anyone English, despite Mark Bullingham revealing that they spoke to 10 candidates. Howe has confirmed he was not even contacted.

The hard numbers are even more concerning. Howe is one of just three English managers in the Premier League right now, and one of just seven over the last decade to have finished in the top half of the table. Even the Championship is moving towards a majority of foreign coaches. You don’t even have to get into debates over whether an Englishman should manage England to find something curious here. The numbers don’t really make sense.

England is a wealthy country that has a population of almost 60 million, with one of the strongest football cultures in the world, as well as a huge football infrastructure that also hosts the most popular domestic league in the world. All of those factors have resulted in St George’s Park and a complete overhaul of the FA’s ideology over a decade. The federation has rightly been lauded for their work after repeatedly reaching major finals.

It is consequently baffling that none of this is producing coaches that the FA feel they can pick from. It really isn’t normal for a football country of this size. Howe and Graham Potter are good but they’re nowhere near making you take notice, like Tuchel. An obvious question is why?

The answer cuts across a lot of modern debates, from how you approach tournaments to the issue of an independent football regulator. Some would argue that it’s unfair to expect the infrastructural overhaul to produce such coaches after a mere decade. Tuchel himself is proof to the contrary. He was one of a huge generation of modern German coaches that started to be produced less than five years after the country’s own infrastructural overhaul around 2002. It has been the same in Spain and Portugal.

A common theme of this week has similarly been that coaching courses are much cheaper in those countries.

That isn’t really a factor as regards to the numbers, though. The reality is the opposite. Despite the price, there are huge waiting lists. Many coaches, like Howe, go to other countries because it’s cheaper and easier. The Spanish-born Mikel Arteta, who at one point said he would consider a call-up for England, was one of a number of big names to do his badges in Wales.

Senior development staff in Uefa would contend that such interest is because the FA’s coaching is “definitely among the top five in Europe” when it comes to providing education for the whole game rather than just the elite. This can directly be seen in the number of quality players produced by England; a group that is now the envy of the football world. It has produced star after star, which is what made the job so attractive to someone like Tuchel.

That is also where the FA’s vaunted plan has come to a crux.

England has coaching that produces elite players but not, ironically, elite coaches themselves.

Figures from other countries are more critical about that. The comment in Italian football is “what English coaching?” The last two European Championships finals emphasise the array of flaws.

England had the talent and the wider managerial outlook, but not the fine details or the grander tactical vision. In the Euro 2020 final, the Italian side felt that a better coach would not have allowed them into the game. They were particularly critical of the use and timing of subs, especially as regards what it said about England and Gareth Southgate’s reading of the game. That isn’t to disparage Southgate specifically, since he brought other qualities. It’s that those shortcomings are part of a trend.

In Euro 2024, Spain could appoint a relative managerial unknown in Luis de la Fuente – a Spanish Lee Carsley, if you like – and still win. That was because they had this core national tactical ideology, that both underpins everything and amplifies everyone.

It’s why there is a global demand for Spanish, German and Portuguese coaches but not English ones.

“If you are looking for elite coaches,” one executive says, “England isn’t a key market.”

That difference also points to a cultural issue beyond the FA, that further inhibits its coaching products. “England has loads of qualified coaches,” the same executive confides. “But it’s not about the qualification, it’s about how the football culture you grow up with melds with that coaching education. It’s the details and what you’re immersed in.”

The very articulation of a Spanish or German football idea comes from environments where it is more natural to discuss the game in depth, which also has a multiplying effect. Portugal is meanwhile on its second coaching revolution. It has already moved on from the Jose Mourinho era, which admirably introduced the idea of coaching as an educational degree, but resulted in defensive football. Managers like Ruben Amorim have now come out of that system to practice more progressive modern approaches, particularly taking notes from German pressing. It is the development of a totally new ideology in what has been quite a short time. That can be a lesson for the FA.

Qualifying for Uefa A and Pro licenses in Portugal is even more competitive, too, and their federation insists on a high number of hours of coaching – much more than England – before you can even apply.

There is an obvious irony in how Portugal is arguably the next biggest football country after England to have appointed a foreign coach, but many say that was down to something simple – and political. Roberto Martinez had a plan for Cristiano Ronaldo in the way other potential appointments like Mourinho didn’t.

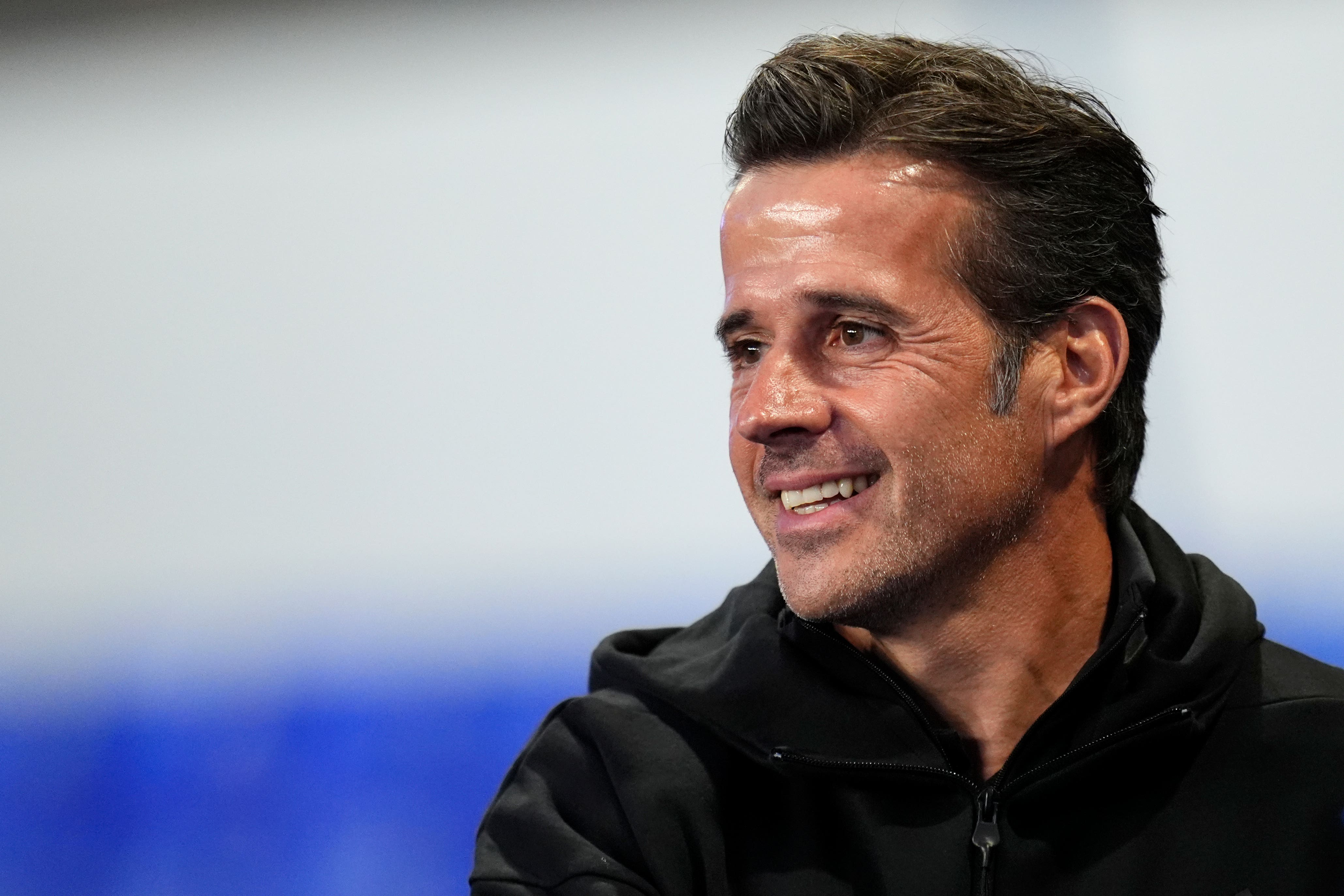

There’s an argument that Portugal’s own coaches were unwilling to go down that road. While finances also played a part: two (Marco Silva and Nuno Espirito Santo) are in better-paid jobs in the Premier League.

The FA also suffers because the country’s main football competition is not really an English league but a global league that happens to be in England. Its ownership is international and their interest is in commercially growing clubs to international size, which means they just want the best coaches – no matter where they’re from. Hence its managerial make-up is four Spanish, three English, two Dutch, two Portuguese, one Australian, one Austrian, one Danish, one German, one Italian, one Northern Irish, one Scottish and one Welsh.

The issue mirrors the Premier League’s role as regards regulation. It is the most powerful entity in England due to its financial size alone, but has little interest in regulating the wider game. By the same token, it has little obligation to appoint English coaches and improve them. That effect has inevitably bled into the Championship.

Some now wonder whether the top two divisions could impose a similar programme to the Elite Player Performance Plan, but for coaches.

For now, it means few English managers are getting chances to even test their abilities at the top level. It gives the FA little choice.