Flutter’s Chief Executive Peter Jackson publicly apologized for failing to intervene, saying the company had a responsibility to do so “when our customers show signs of problem gambling.”

Over the next few years, another one of Jackson’s customers — this time in America — spiraled even further out of control, gambling millions of dollars of stolen money with Flutter’s U.S. brand FanDuel. Amit Patel, then a mid-level finance manager at the Jacksonville Jaguars football team, deposited $20 million of his employer’s money into his FanDuel account between 2019 and early 2023, and then lost most of those embezzled dollars, according to court documents. Patel and the British animal-shelter chief each pleaded guilty to fraud.

Amit Patel embezzled money from his then employer, the Jacksonville Jaguars football team, to fund his gambling. He is seen here in a picture contained in a sentencing memo filed in court by the U.S. government after Patel pled guilty to fraud.

Despite the enormous sums, FanDuel didn’t question the source of Patel’s funds until late 2022, his lawyer, Alex King, told Reuters. Patel’s annual salary was less than $90,000, King said. FanDuel not only didn’t intervene as Patel’s losses snowballed, according to King, but also assigned Patel a VIP customer representative who encouraged him to continue gambling.

Flutter and FanDuel didn’t answer questions about Patel.

In Britain, where online gambling is more established than the United States, Flutter and other bookmakers have in recent years acknowledged some of their previous practices risked causing harm and ended those practices. Some have also publicly accepted a responsibility to protect customers from problem gambling as cases of addiction, suicide and gambling-related crime stacked up there.

In Britain, the two gambling giants volunteered to curtail VIP programs that induce customers to spend more after acknowledging the potential for harm to gamblers. And Flutter introduced protections for bettors under 25 years old, having said “younger people can be more vulnerable to experiencing gambling harm.” Critically, advocates for gambling addicts say, the firms also accepted that keeping customers safe requires monitoring the affordability of their bets and intervening when there are signs of problem gambling.

The two companies haven’t acknowledged that they should be subject to some of the same requirements in America, such as affordability monitoring. What’s more, in the U.S. — where public and regulatory scrutiny of the online gambling industry hasn’t been as intense as in Britain — they employ some practices forbidden by regulators in Britain, including offering some online slots features such as enabling gamblers to set the game to play automatically without even having to watch the screen. Such features encourage gamblers to lose control of their gambling and suffer unaffordable losses, consumer protection advocates say.

Betting online in the U.S., like bricks-and-mortar casinos, is largely regulated on a state-by-state basis. The key difference is that online gambling involves new types of products and bets can be placed round the clock via a mobile phone, a factor that consumer protection advocates say dramatically increases the risk of gambling harm.

In 2020, Flutter CEO Jackson told investors that its UK account managers who oversaw the activities of the most active gamblers weren’t incentivized for the amount customers spent, a point he stressed as “important.” It’s a “way of ensuring we don’t get on the wrong side of that affordability point,” he said.

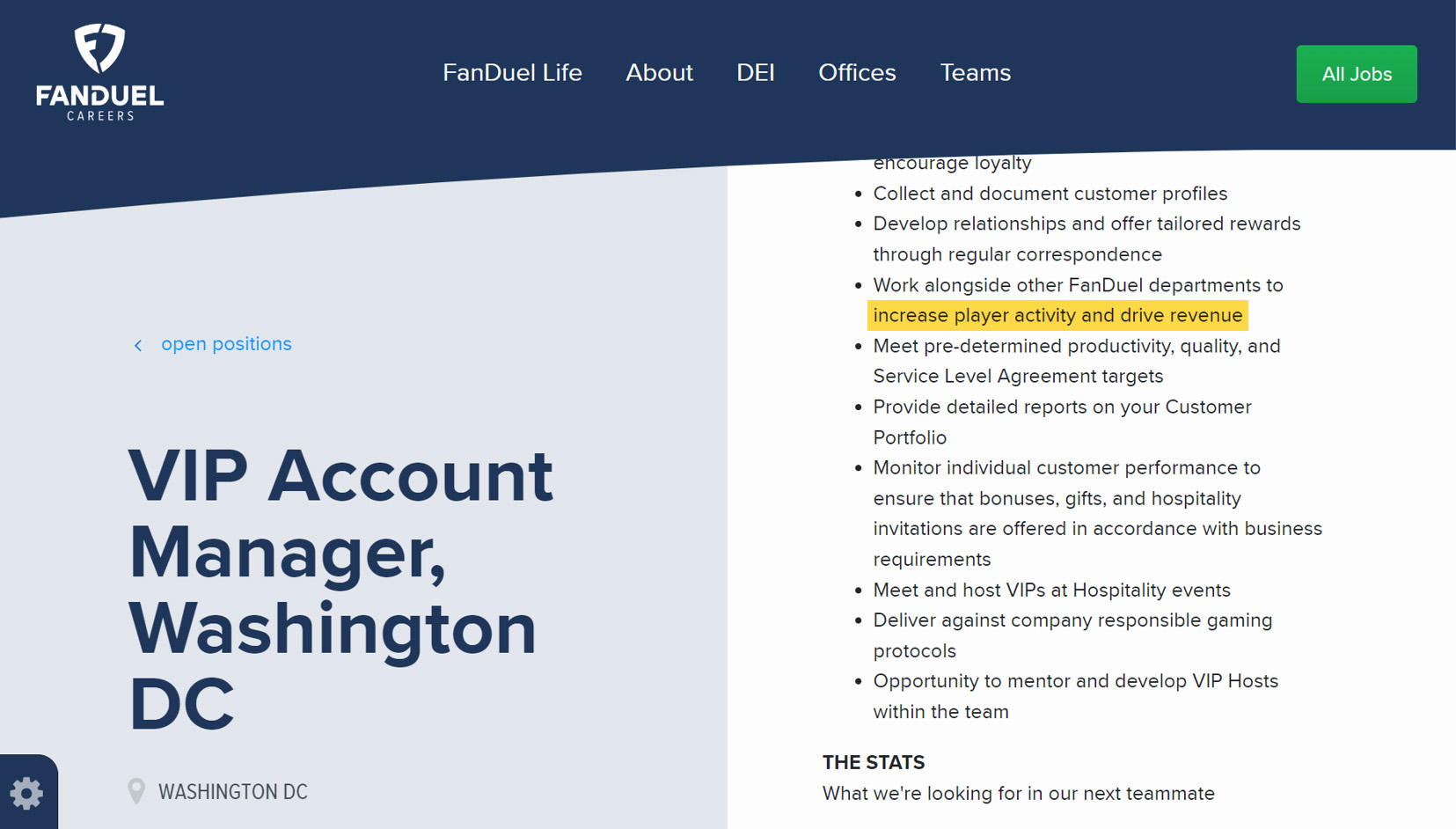

In the United States, advertisements for roles as VIP account managers on FanDuel’s website visible as recently as April 2024 said candidates would be expected to “increase player activity and drive revenue.” After Reuters asked about the ads in April, FanDuel removed the phrase from its VIP job ads.

And Flutter in 2021 introduced a limit for UK customer bets on online slots games to £10 per spin, or about $13. The world’s largest online gambling company by revenues has said it did so because it had identified a trend in its data that “suggested that customer risk levels may increase more sharply” among clients wagering more.

Online betting companies offer incentives to lure new customers such as bonus bets, which are credits that can be used for wagering. REUTERS/Dado Ruvic/Illustration

When asked by Reuters why Flutter uses practices in the United States that the company acknowledged as potentially harmful in Britain, Jackson said Flutter is committed to high standards of customer protection in all markets it operates in. “We help engineer and lead a race to the top in terms of the standards,” said Jackson, 48, speaking to Reuters in May at the sidelines of the company’s annual meeting in Dublin.

Flutter said in a statement the company operates “in strict accordance” with rules and regulations in the jurisdictions it is licensed in, and implements strategies tailored to the local markets it serves based on maturity and the competitive landscape.

American football star Rob Gronkowski accompanied Flutter CEO Peter Jackson at the company’s New York Stock Exchange listing earlier this year. REUTERS/Brendan McDermid

BetMGM co-owner Entain, in a statement, said it operates in dozens of markets and “it would simply not be feasible or commercially viable to have a ‘one size fits all’ approach.”

“It is true to say right now the U.S. is in its infancy, and there is less of the kind of protections that you see in the UK,” Entain’s Chief Financial Officer Rob Wood told Reuters in April. He defended BetMGM’s practices, saying “we don’t apply low standards anywhere.”

Together, FanDuel and BetMGM account for about half of U.S. online net gambling revenues.

Patel, 31, is currently serving a six-and-a-half-year prison sentence. It should have been clear to FanDuel “that he was gambling very large and growing amounts and having excessive losses,” said his attorney, King. “And they did nothing to dissuade or try to prevent him, or anything but encourage him to continue to gamble.”

U.S. Representative Paul Tonko, a New York Democrat who has drafted a proposed bill to regulate the online sports betting industry in America, said the Reuters examination suggests the companies are knowingly putting their U.S. customers in harm’s way.

In March, Tonko announced plans for a bill that would require sports betting operators to introduce measures to help prevent gamblers spending more than they can afford, including not accepting deposits via credit card and assessing a customer’s financial circumstances before accepting large wagers. Tonko told Reuters the companies opposed his bill. Neither Tonko nor the companies provided Reuters with any specifics.

It is true to say right now the U.S. is in its infancy, and there is less of the kind of protections that you see in the UK.

Entain Chief Financial Officer Rob Wood

Several analysts told Reuters they don’t expect big regulatory pressure anytime soon for the online operators in America. Some state legislators have proposed advertising restrictions, but for now, the analysts said, state lawmakers are more focused on the potential tax revenue they can raise from online gambling than on curbing the industry.

Jackson, who became Flutter’s CEO in 2018, told Reuters he didn’t foresee federal regulation of the industry in America.

Entain’s Wood, who is 44 and like Jackson is British, said he expects the industry in America to voluntarily improve player protections over time: The market is “still maturing and it’s still working out the best way to self-regulate.”

Common measures aimed at protecting gamblers offered in the United States by FanDuel, BetMGM and others include company ads urging self-restraint, and offering clients the ability to set deposit limits or to “self-exclude” — temporarily suspend their accounts for a period of time. FanDuel and BetMGM also fund research into gambling behavior in America.

However, experts on gambling addiction say these types of measures are insufficient because addicts are not good at exercising self-restraint — a position Flutter and Entain have acknowledged in Britain.

The United States has seen rapid growth in wagers placed online in recent years, fueled by the legalization of sports betting. REUTERS/Eduardo Munoz

Britain requires online betting companies to use data on client behavior to identify potentially compulsive or problem gambling. To help identify people who gamble beyond their means, operators also must seek evidence of the source of large deposits to try to prevent the use of stolen money. Companies also are expected to look at publicly available information, such as what someone does for a living or court judgments on unpaid debts, to check if a customer suffering significant losses can afford it based on their income or wealth. And, if the customer isn’t clearly in a position to afford the losses, the companies are expected to probe further, such as potentially requesting payslips.

Some consumer advocates say that anecdotally they have seen fewer instances of extreme problem gambling being missed and both Flutter and Entain have reported more frequent client interventions. Analysts also say both companies are shifting their client focus in Britain to recreational gamblers, away from very active ones.

Earlier this year, Flutter estimated the impact of new regulations currently being rolled out in Britain will cost up to 250 million British pounds each year in lost revenue.

Joe K, a recovering New Jersey gambling addict who spoke on condition that his surname not be used, said he lost around $250,000 of an inheritance by gambling online during a relapse in 2020.

The 58-year-old former broker and father of two said he placed bets with FanDuel, BetMGM and smaller operators during his spree, playing online slots and poker and placing sports wagers. The games included some slots features barred in Britain, such as high-speed play and $100 spins, he said.

He doesn’t expect online gambling operators to give up growth opportunity voluntarily. “They make their money off compulsive gamblers,” said Joe.

FanDuel and BetMGM are flooding American sports fans with advertising, including featuring celebrities such as the former NFL player known as “Gronk.” He is seen here in a screengrab from a video from FanDuel’s YouTube account.

Movie star Jamie Foxx is a BetMGM brand ambassador. In one ad he encourages users to try betting on a variety of outcomes during a game “every time they throw the ball, kick the ball, dribble the ball.” This image was made available to media via Entain’s website. Credit: BetMGM

Representatives for Foxx and Gronkowski didn’t respond to requests for comment.

FanDuel and BetMGM have credited their rapid growth in America in part to the experience they bring from the UK. Among know-how honed in Britain is an emphasis on complex wagers such as parlay bets, which allow people to bet on multiple things happening together with the promise of a bigger payout. Parlay bets typically are much more profitable for companies because customers are less likely to win.

Online sports bookmakers alone took $114 billion of U.S. bets in 2023, according to the American Gaming Association, the industry’s main lobbying group. Across both sports and casinos online, gross gaming revenue — or bets taken minus winnings paid out — was $16.9 billion last year, more than double just two years earlier and up from $1 billion in 2019. That could reach $65 billion of revenue by 2033, according to Goldman Sachs forecasts.

The focus on the American market has come as increased regulations and self-policing of online gambling in the United Kingdom squeezed the companies’ profitability there. Both online sports betting and online casinos have been legal and regulated far longer in Britain than in the United States.

Online gambling emerged in Britain in the 1990s, and the country became the largest regulated online market by revenue in the world, until being overtaken by the United States in the past couple of years.

British sports-betting revenue in particular has been trending down in recent years, which analysts attribute largely to a UK regulatory tightening that began in the late 2010s after alarming cases of gambling addiction.

In recent years, the bosses of Entain and Flutter have had a financial incentive in the United Kingdom to adopt measures that directly curtail problem gambling. Jackson’s annual bonus is tied to Flutter becoming less reliant on deposits from people who go on to self-exclude — a key indicator of problem gambling. Similarly, Entain CFO Wood’s bonus hinges on identifying UK gamblers who display markers of gambling harm and intervening to help them.

But the two executives’ bonus plans don’t require their U.S. subsidiaries to identify and intervene with problem gamblers. Rather, both Flutter’s FanDuel and Entain’s BetMGM only need to roll out tools that encourage players to exercise self-restraint to allow the two executives to get full payouts from their U.S. market business.

Neither Flutter nor Entain answered questions about the bonus plans.

Another area where Flutter’s approach has diverged either side of the Atlantic is towards under-25-year-olds, who the company has said are more vulnerable to gambling harm.

In 2022, Flutter introduced net deposit limits of 500 pounds per month in Britain and €500 in Ireland for customers under the age of 25. It wasn’t because regulations forced it to do so, Flutter said in an announcement about the move, but because “it is the right thing to do.”

But in the United States, Flutter doesn’t place such limits on the age group.

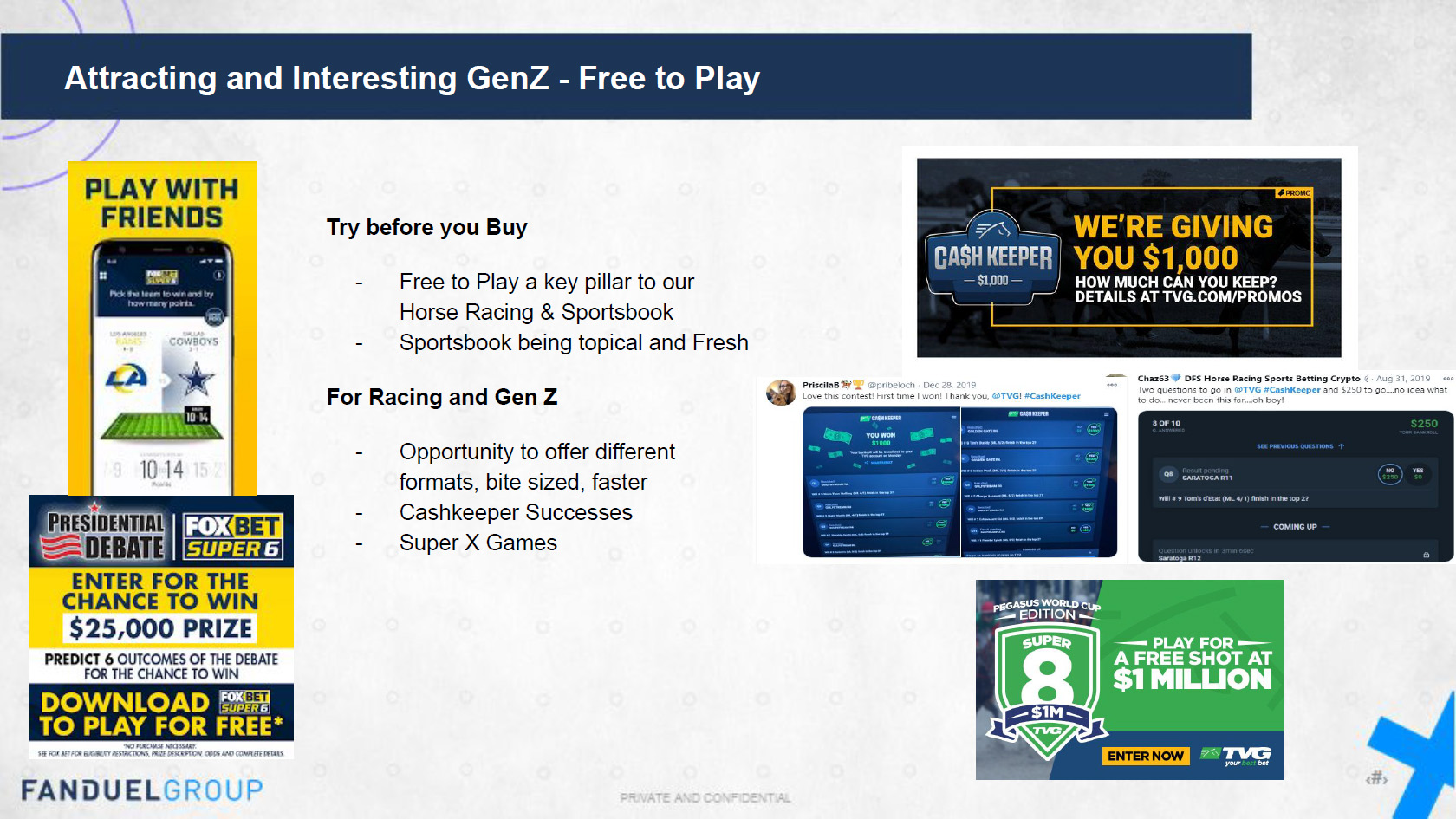

Another measure the company has said it voluntarily introduced in the UK is the use of technology to help ensure its social media ads are not viewed by under-25-year-olds. In the United States, it has actively used social media to appeal to Generation Z, signing deals with online influencers popular with this group, according to a presentation called “Racing for Gen Z” given by a FanDuel division head at an online conference in January 2021. In early 2021, the oldest of this generation would have been 24. The presentation says the company only signs customers aged 21 and older.

FanDuel’s efforts to appeal to Generation Z are outlined in a company presentation at an online conference in 2021, via World Tote Association’s website.

When the New York State Gaming Commission proposed banning sports-gambling advertising around university campuses last year, FanDuel protested to the commission, saying restrictions should only apply to campus grounds, according to the New York state register. Its objections were unsuccessful.

Flutter didn’t respond to questions about the differing approaches.

FanDuel told Reuters it produces videos and social media stories to tell under-25s in the United States about the risks of problem gambling.

Felicia Grondin, executive director of the Council on Compulsive Gambling of New Jersey, told Reuters the extra risk faced by young people is real. She said that since online sports betting was legalized in her state, following the Supreme Court’s overturning of a federal ban in 2018, contacts with her helpline nearly quadrupled to more than 2,200 calls, texts and chats in 2023. The share of younger gamblers contacting the group has doubled over that period.

One practice both Flutter and Entain took across the Atlantic from Britain is the appointing of “VIP” personal relationship managers to their more active customers.

Traditional VIP managers at U.S. brick-and-mortar casinos focus more on treating high rollers well during their visits — making sure they are happy with their rooms, treating them to meals or helping secure show tickets.

At the online giants, VIP programs offer gamblers incentives like free bets to encourage them to wager more. They also “cross sell” — persuading players to try different types of bets or games such as online slot machines, according to interviews with gamblers, current and former VIP managers and a review of jobs advertisements by the firms.

Around a decade ago, British politicians became concerned about a rise in gambling-linked fraud and suicides involving online VIP customers. Some politicians accused operators of using VIP managers to convince customers to bet more than they could afford to lose.

The role of VIP managers includes increasing customer spending, according to job advertisements such as this one posted on FanDuel’s website, captured by Reuters on April 6, 2024.

Entain, like Flutter, has publicly acknowledged the risk in the UK of signs of problem gambling being missed if account managers are incentivized for the amount customers spend.

In 2020, the then head of GVC, as Entain was known at the time, told British lawmakers that VIP programs had become “too aggressive” and incentivizing client managers to drive revenue had been a “failing” in the industry.

In the United States, prospective VIP managers for Flutter’s FanDuel and Entain’s BetMGM have specifically been told their role is to increase customer spending, according to job ads posted by both firms and interviews with two former BetMGM VIP managers.

An advertisement on FanDuel’s website in December for a “VIP Area Director” for the mid-Atlantic region stated a purpose of the role was to “grow the value of the VIP customer base” and that their team of client representatives’ key performance indicators included “average player value.”

And, recruitment notices visible in recent months on BetMGM’s website for online casino-host job openings in the United States said the new hires would be expected to “generate incremental gaming revenue” from VIPs, “with the aim of extracting maximum value.”

LinkedIn postings by current and former VIP managers at FanDuel and BetMGM boast of their record of boosting client spending.

FanDuel spokesman Chris Jones said VIP managers’ pay is not directly linked to deposits from their clients. He said the reference in the job ads to driving revenue reflected a broader expectation for VIP managers to support growth. He declined to say if VIP teams had revenue or “share of wallet” targets.

Neither Entain nor BetMGM addressed questions on VIP programs.

There’s a very fine line between VIPs and someone with a gambling problem.

Former BetMGM VIP manager Josh Giaramita

As in the UK, American VIP clients typically aren’t the limousine-driven high roller depicted in Hollywood movies, according to industry insiders, who say such individuals are usually much more modest earners. For sports betting, they were people who, on average, made wagers worth $5,000 to $10,000 per month and lost a minimum of $1,000 per month, according to an ex-BetMGM VIP manager, who asked not to be identified because he still works in the industry. He said his aim wasn’t to encourage VIP clients to bet more than they could afford to lose, but he acknowledged his team had revenue targets.

Another role for U.S. VIP managers is to “reactivate” high-spending clients who have stopped betting, industry insiders said. Josh Giaramita, a former BetMGM VIP manager, said measures included sending emails to inactive clients and on occasion, crediting their betting accounts to encourage them to play again.

Giaramita said he looked out for signs of problem gambling. But he added: “There’s a very fine line between VIPs and someone with a gambling problem.”

Sign up here.

Reporting by Tom Bergin; Additional reporting: Padraic Halpin; Illustration: Catherine Tai; Photo editing: Simon Newman; Design: Jillian Kumagai; Edited by Cassell Bryan-Low and Tom Lasseter

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.