By Deborah Nicholls-Lee,

MIT and Halsey Burgund

MIT and Halsey Burgund“The effect that scares me most is not that we’ll be fooled by fake photos but that we’ll ignore the real ones” – how photographers are dealing with shifting perceptions of reality.

“I think it’s getting harder to know what is true,” says Jago Cooper, the director of the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich, which is part-way through a six-month series of interlinked exhibitions based around the question What is Truth?

It’s a theme that’s being taken up by a number of museums. In Maastricht, Fotomuseum aan het Vrijthof’s Truth is Dead is currently displaying Alison Jackson’s amusingly misleading photographs of celebrities, for example; while Foam Amsterdam is exploring how the intersection of art and technology can change our perception of reality with Photography Through the Lens of AI.

“People genuinely want to know how they know what is true in the world today,” says Cooper. “Truth is so hard to find and it’s a really interesting question.” Unsurprising, then, that it’s become a prevalent theme for many contemporary artists, eager to open up conversations about the trustworthiness of visual media.

Richard Mosse

Richard MosseOne such artist is the Irish film-maker and photographer Richard Mosse. His photograph Poison Glen (2012) from The Enclave series features in the Sainsbury’s Centre’s newest exhibition The Camera Never Lies: Challenging images through the Incite Project. The eastern Congolese landscape in the frame ought to appear as green as the Donegal valley it is named for, but by using infrared film, a device normally intended to reveal information, Mosse has instead deceived us. A landscape populated by armed rebels, who are part of a conflict which has cost over 5 million lives, is turned an inviting sugar pink: the nightmare now looks like a fairytale.

Stuart Franklin/Magnum Photos

Stuart Franklin/Magnum PhotosAlso in The Camera Never Lies – which re-evaluates the most iconic images of the past 100 years – is Stuart Franklin’s The Tank Man (1989). In the photo, a lone protester in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square stands in the path of tanks just minutes after the Chinese authorities gunned down anti-corruption and pro-reform demonstrators.

Over time, different truths have been attached to the image – a key part of the exhibition’s purpose, exploring how photos have become the memory bank of our lives and how far they are a true reflection of history or merely the images that form our perception of it. Initially, Franklin told Vice in 2020, the captured moment was “a very useful event politically … because, in a sense, it was all about restraint. They [the Chinese authorities] didn’t kill him … and it managed to play itself over the top of all the pictures of dead bodies.”

Later, as the collective memory of the massacre faded, it became more expedient to airbrush it out of history. “In the Western world, it’s an iconic image of protest and the dangers of autocracy and the suppression of free speech,” says Cooper. “Whereas, within China, you don’t see the image at all.”

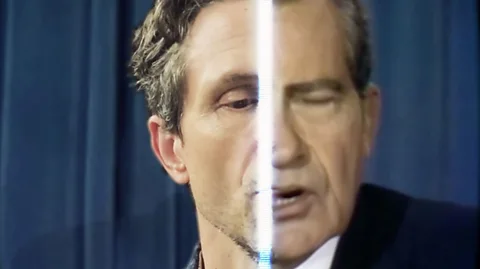

MIT and Halsey Burgund

MIT and Halsey BurgundThe Emmy award-winning In Event of Moon Disaster (2019), created by American new media artist Halsey Burgund and British digital artist Francesca Panetta, is also on show at the Sainsbury Centre. The film, shown on a vintage TV as part of an immersive installation of a 1960s living room, plays on the many conspiracy theories surrounding the first Moon landing by presenting an alternative version of reality and asking if viewers can spot a deepfake.

Some elements are real – the script prepared in case the astronauts on Nasa’s Apollo 11 mission in 1969 died, for example – while others, such as the deepfake of President Richard Nixon reading out the script created by synthesising an actor’s voice using AI, are not. “All of the footage we used was real archival footage from Apollo 11,” the quiz explains at the end. “However, we used techniques of misinformation to tell a story vastly different from what actually happened.”

“The effect that scares me most is not that we’ll be fooled by fake photos but that we’ll ignore the real ones, or choose which to believe based on our presumptions,” Athens-based photographer Maria Mavropoulou tells the BBC. In 2023, interested in how new image-making tools may shift our perception of reality, she used the prompt “A Self-Portrait of an Algorithm” to invite AI to introduce itself.

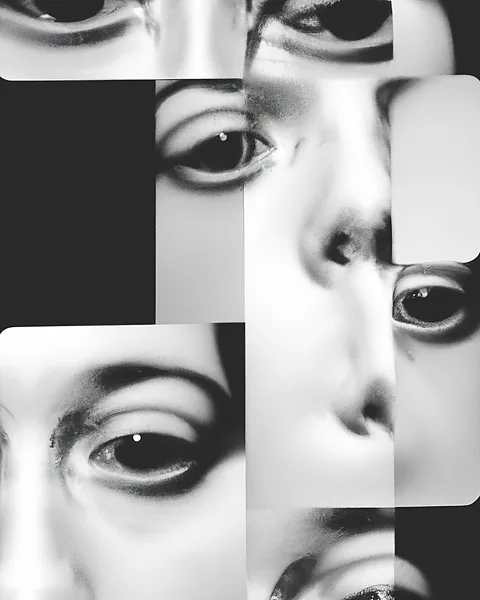

Maria Mavropoulou

Maria MavropoulouThe portraits that emerged, some of which are currently on show in Photography through the lens of AI at Amsterdam’s Foam Museum, were different every time she asked. AI’s identity was shifting − the truth of what it really was, intangible. “It seems to me that truth is an idea that is sometimes too difficult to pin down and that it is not to be found on the surface of an image,” she says.

For years, Mavropoulou’s own portrait was rarely taken, her itinerant childhood leaving much of her early life undocumented. In Imagined Images (2023), she used what she knew about her family history as prompts for text-to-image software and created the family photo album she never had. At first, the photographs seem unremarkable, but looking closely at A five-year-old girl blowing out birthday candles, we see that the children’s faces are distorted, a bowl floats off the tablecloth and “party food” has become a hybrid of cake and chips.

Maria Mavropoulou

Maria MavropoulouThe album’s images are made up of what she calls “statistical truths” based on typologies, such as “mother”, “party” and “holiday”, synthesised from a multitude of data sources. Yet though real photo albums have “no clear intention to lie or deceive”, the story they tell is also unreliable, says Mavropoulou. “Only happy moments, celebrations and milestones make it in the album, while difficulties, struggles, and loss are left unphotographed.”

Nouf Aljowaysir

Nouf AljowaysirThe in-built biases in AI are also the subject of Where Am I From (Ana Min Wein?) (2022), a short film and visual diary created by New York-based visual artist Nouf Aljowaysir. The work forms part of the Saudi-born artist’s exploration into a genealogical journey led by two narrators: the artist and AI. “Through my mother’s beautiful story, I felt belonging,” she tells the BBC.

Nouf Aljowaysir

Nouf Aljowaysir“However, as I processed these images through computer vision techniques, this revealed failures in the form of generalisations and stereotypes, uncovering systemically embedded prejudice within commercial AI tools.” Desert scenes were interpreted as military operations, for example, and AI cannot decide if a hijab is “a poncho”, a “costume” or a “tent”. There’s an element of comedy and surprise, but the overall effect is unsettling. “The film shows how artificial intelligence sees my culture through a simplistic and biased Western lens, reducing my identity, culture and erasing collective ancestral memories,” she says.

BBC Verify

With misinformation on the rise, the BBC has launched a brand aimed at countering fake news. BBC Verify is dedicated to examining the facts and claims behind a story to try to determine whether or not it is true, bringing together journalists with a range of forensic investigative skills and open-source intelligence (Osint) capabilities. As well as fact-checking, verifying video, countering disinformation and analysing data, the team transparently shares their evidence-gathering with the audience, explaining complex stories in the pursuit of truth.

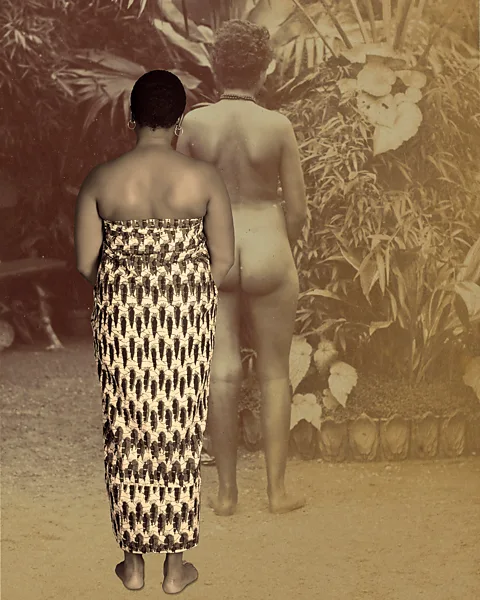

Reclamation of the Exposition (2020), by British-Nigerian visual artist Tayo Adekunle, exposes the colonial lens behind the 19th-Century “truth” about the black female body expressed in the archival images of Prince Roland Napoleon Bonaparte. “The Bonaparte images were actually taken in the botanical gardens in Paris, and these were South African women who were brought over and put on animal skin [made to pose standing on it] to replicate an exotic environment,” Adekunle tells the BBC.

Tayo Adekunle

Tayo AdekunleThese staging elements also included removing the women’s clothes. Their images became curios for what she describes as “pseudo-science” and were distributed as pornographic postcards. “They perpetuated the idea that black women were more sexual and that people from Africa were savages because they didn’t wear clothes,” says Adekunle.

Her decision to place herself in the image and mimic their pose is a gesture of solidarity and a symbol of the timelessness of these mistruths. “There’s a power struggle that happens when you have a photographer and a sitter, and even more so, when that photographer is a white man and the sitter is a black woman,” she says. “I didn’t want the images, this legacy in the relationship, to feel like it was only existing in the past.”

While misrepresentation, as in the case of Bonaparte, can be disturbing, deception is something different in the work of British photographer Alison Jackson more than a century later. In her solo show at the Vrijthof, Royal Selfie appears to show Elizabeth II taking a family snap, while Trump and Money features an open-shirted Donald Trump lookalike with his arms around two women, and is one of several images in the show that play with public perceptions of the US presidential candidate.

Such realistic images – placing famous lookalikes in amusing or compromising situations – are a reminder, says the museum, “that we cannot trust our own eyes when it comes to photography”. Even the best-known faces in the world can fool us.

“The truth is dead,” Jackson says. “Nothing we are shown can be trusted; everything can be faked and nothing is authentic.” Jackson’s work was initially inspired by the mourning of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales by a public that had never met her, which she felt exposed a tension between perception and reality. Speaking to Euronews in 2020, she said: “We’ve got mistaken over what is real and what is not and that is what interests me… We’re prepared to go along with a bunch of media narratives – we’re all so surface.”

Truth is Dead is at the Fotomuseum aan het Vrijthof, Maastricht until 15 September.