Gildas Walton was devastated in 2013 to lose his best friend, James Glynn, to suicide. He was even more distraught when he learned of an allegation Glynn had made to his sister before his death.

He told her that he’d been sexually abused by his teacher — a Canadian man named Paul Sheppard — when he was 10 years old, at the prestigious Ampleforth College boarding school in North Yorkshire, England.

Walton has spent more than a decade trying to live with the death of his old classmate, only to recently discover that Sheppard had a criminal record for abusing children before moving to England.

A CBC News investigation found Paul Sheppard was a police officer in Stratford, Ont., for a brief time before being charged with 12 counts of physical and sexual assault against boys in 1986.

He pleaded guilty to six counts of assault, in exchange for the sexual offences being dropped.

Sheppard went on to teach at Ampleforth in 1989, placed in charge of boys the same age as those he abused back home in Canada.

“I’d love to know how they employed him and what checks they did, if any,” Walton told CBC News in June. “It’s fairly horrific to know that somebody who was two months out of probation for similar offences was then reading me stories at night when I was 10.”

Ampleforth College did not respond to CBC’s request for comment by publishing time. Sheppard, through his lawyer, also failed to respond to repeated requests for comment by deadline.

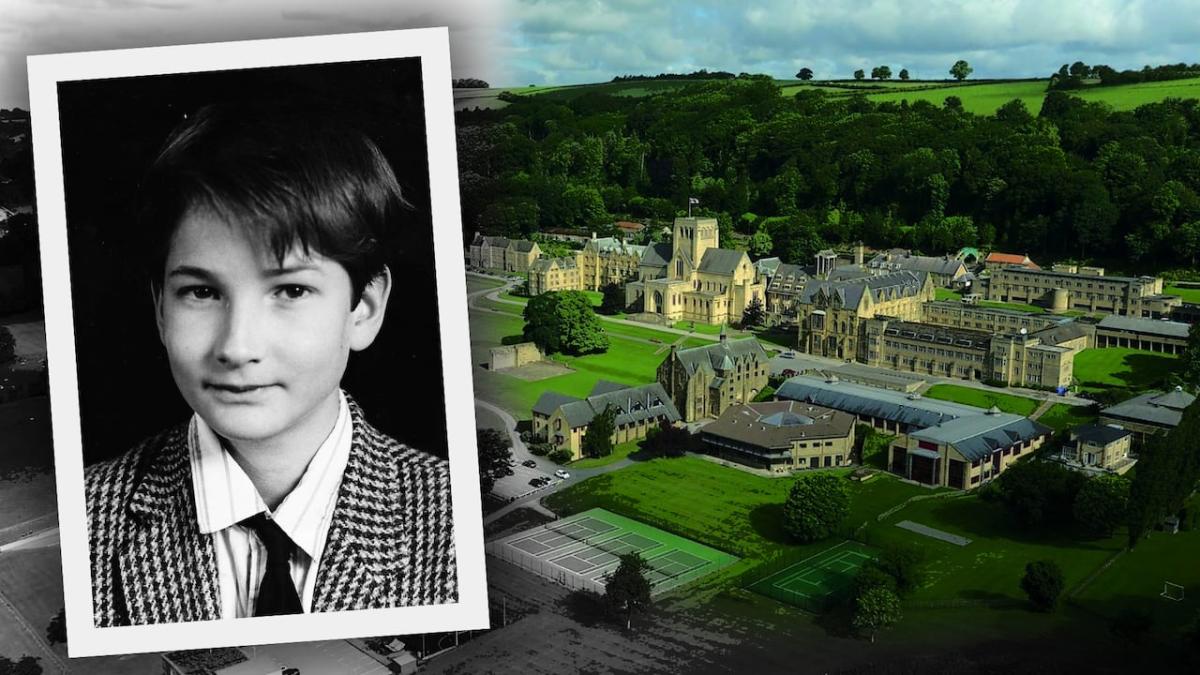

Paul Sheppard was hired as a supply teacher in 1989 at the prestigious Ampleforth College in England. He quickly racked up allegations of inappropriate behaviour with students. CBC News has discovered Sheppard was a convicted child abuser in Canada before going abroad. (Saint John’s School of Alberta, Ampleforth College/CBC photo composition)

James Glynn’s family declined an interview, but said their brother did confide the allegations to them before his death in 2013.

Those allegations led to a police investigation following his suicide. Sheppard was then arrested at Heathrow Airport, after arriving on vacation from a teaching job in Kuwait in 2015, on suspicion of raping James Glynn.

The Crown Prosecution Service opted against laying a charge due to the length of time since the alleged assault, and the fact the key witness was dead.

Walton wasn’t satisfied, and encouraged more former classmates to come forward with their stories about Sheppard’s tumultuous summer term at Ampleforth in 1989.

According to reporting from the Times of London, 11 fed-up kids went to the headmaster, Father Dominic Milroy, in late June of 1989 and reported incidents with their teacher. Milroy called them into his office one by one, with the boys claiming Sheppard kissed them, hugged them and made them feel uncomfortable.

Milroy — who has since died — said the school “could not consider him staying on,” according to the Times, but provided him with glowing references to find work elsewhere.

The school — through statements to other media outlets — has remained adamant that Milroy’s investigation did not turn up any evidence to support claims of sexual impropriety, and that the decision not to renew Sheppard’s contract was mutual.

Walton still disagrees with those assertions.

“They were definitely sexual,” he said of the allegations. “The school just wanted, as it did with all cases back then, to just brush it under the carpet.”

Case fell apart at trial

When the North Yorkshire Police heard from other students in 2015, its probe into Sheppard’s conduct expanded beyond James Glynn. The result was four charges of indecent assault involving three students.

Additional charges were expected involving two other complainants, but were never laid.

The case fell apart on the first day of trial, however, with the judge siding with the defence’s interpretation that the majority of accusations did not meet the standard of “indecent.” Those charges included allegations that Sheppard held a boy down while straddling him and kissed a boy on the forehead while stroking his body.

Ampleforth College is one of the most elite boarding schools in the U.K., costing families more than £46,000 per school year. It has also been at the centre of several sexual abuse and safeguarding scandals. (Ampleforth College/Facebook)

After a brief session in a closed courtroom, all but one count was dismissed. In the end, one accuser was left standing, and the jury was never allowed to hear about the other students.

“The trial was just one boy against one man,” Walton said. “And one man’s word against another in this country is innocent until proven guilty, and that’s not enough, is it?

“That boy thought he was going to trial on that day with five guys all standing up together for what’s right, and he was hung out to dry.”

The jury found Sheppard not guilty on the single count of indecent assault. Walton said he couldn’t blame them for reaching that conclusion, given the limited information before them.

The jury was told about Sheppard’s glowing references, but not about the complaints that preceded his exit. They were never told about the other students, including James Glynn’s allegation of rape.

Questions remain

Walton — who was not abused at Ampleforth — struggled to cope after how the trial unfolded. On top of that, he’s now left to wonder how Sheppard became his teacher in the first place.

Sheppard pleaded guilty to six charges of assault in 1987. He admitted to spanking boys as punishment, some he met through police work and others through volunteer programs.

He was given two years’ probation, and worked toward an education degree in Newfoundland and Labrador throughout that period. His criminal record also didn’t stop him from teaching at schools in North America, Europe, Africa and Asia.

If there was a consolation to what Walton describes as a bungled case in the U.K., it was that it prompted a former student of Sheppard’s in Canada to come forward.

Steacy Easton started at Saint John’s School of Alberta in 1993 — a shy child who struggled to fit in with the unorthodox curriculum. (CBC, submitted by Steacy Easton)

Steacy Easton followed coverage of the case, and contacted the RCMP to share their story of sexual abuse during the 1993-94 school year at Saint John’s School of Alberta.

Sheppard was eventually convicted on two charges in 2021, and given a four-year sentence. He was granted day parole in July, and is serving out his sentence at a halfway house in Ontario.

During the parole hearing, he acknowledged his prior convictions as a police officer — something prosecutors were unaware of in his U.K. and Canadian trials.

Walton has long wondered how Sheppard was chosen by the Ampleforth brass to begin with, given he was a fish out of water as a 26-year-old secular Canadian in a school of Benedictine monks.

Now he questions if they knew he was a convicted serial child abuser before ever being hired.

“I don’t know how he’s got away with it,” he said. “He was sadistic. We were all terrified of him. He wasn’t just an abuser, he was a beater. He was crazy in his eyes. He would flip. He was a horrible man.”

Download our free CBC News app to sign up for push alerts for CBC Newfoundland and Labrador. Click here to visit our landing page.