Forgive us the easy layup question we asked Stephen Curry on our shoot with him back in January for the June cover of Golf Digest.

“Is there anybody in the NBA who can beat you in golf?”

“Negative. No chance,” Curry said. “I’m taking those bets all day long.”

So let’s accept that as a given: Curry is the best golfer in one of the leading professional sports that isn’t golf. But how close is that to the guys who play for a living? How do the mechanics of Curry’s swing compare with the best moves in the game? And could he—just maybe—play pro golf someday, when his NBA career is over?

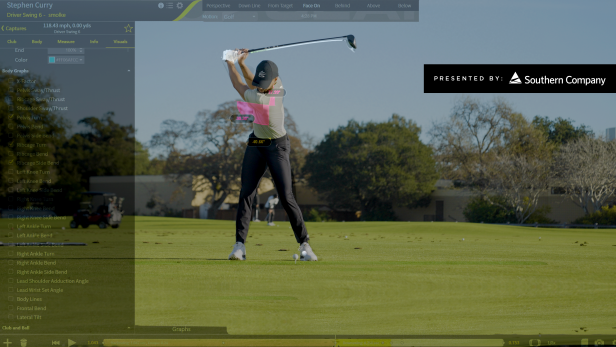

To get some answers, we arranged a swing-analysis session by GEARS Sports, golf’s most sophisticated 3D motion-capture system. It’s the only process that measures what both the body and club are doing throughout the swing. It collects about 2,000 images per swing, and then shows the golfer as a computer-generated avatar overlaid with data points.

When Curry met us at Stanford University’s Siebel Varsity Training Complex the morning after a 133-118 loss to the Toronto Raptors, he had fully turned his attention to his second-favorite (close second) sport. We were ready to put his tilts, turns and timing to the test.

Michael Neff, the founder of GEARS who has measured the swings of nearly 500 tour-level players, was running point. Neff fitted Curry with 28 wireless markers, from the top of his hat to his shoes, plus six more on each of his clubs. At one point, Neff noted a scar on Curry’s right elbow: “What’s this?” Curry replied, “Probably a foul that didn’t get called.”

During the session prep, Curry explained that his game gets better as he gets closer to the green, his killer miss a pull-hook with the driver. His longer irons sometimes flare to the right, but his confidence with the short game is high. USGA Handicap Index: +1.

“My wedge game is solid, but I do like to tinker with putters,” he said. “But it’s all good right now. I’m 18 months with the same putter—that’s a big deal for me.”

Curry has been working with swing coach Alex Riggs, who is based in Dubai, on rotating his hips more on the backswing. His swing used to be upper-body dominant, so they’ve tried to activate his lower half. They’ve also addressed his tendency to cup his left wrist going back; a cupped wrist means an open clubface. Curry said they’ve made progress in the past year.

Last July, Curry had the highlight of his golf career when he won the American Century Celebrity Golf Championship, in Lake Tahoe, a 54-hole event that brings together boldface names from sports and entertainment. And he did it with some swagger, making a hole-in-one in Round 2 and dropping a clinching eagle putt on the last green.

With the markers installed on Curry’s body and clubs, it was time to start testing. Neff had placed eight cameras around the room to record how each marker moved, with no tiny motion left unchecked. Curry hit 8-irons first, then drivers, and after several swings, data started flooding the monitor like something out of The Matrix.

ABOVE: Using 2,000 images per swing, GEARS transformed Stephen into an on-screen avatar.

Curry soon got a first look at himself as a GEARS avatar. (He’d worked with motion capture before, when making NBA video games.) Watching the big screen on the wall, he waved his arms around, did a little dance, even mimicked his famous jump shot, with the avatar on screen mirroring his every move.

“This level of detail is insane,” Curry said. “I’m nerding out on this.”

Neff started with some top-line analysis, noting that Curry’s posture at address was well balanced and—no surprise—very athletic. His first move off the ball also looked spot on, with the club tracking in a neutral arc and the clubface staying square. “You’d have to have a really good reason to change anything here,” Neff said.

At the top of the swing, Curry’s left wrist is essentially flat to his left forearm (no cupping), which puts the clubface in a good position for the downswing. With his hips turned 41 degrees at full stretch, he was right at the average of tour players (40) that GEARS has measured. His shoulders were turned 98 degrees, compared to 97 for the tour pros.

ABOVE: Curry’s backswing checks out, with his body, arms and club near perfect at the top.

“I love this backswing,” Neff said. “Great rotation, clubface basically neutral, and the center of the ribcage is directly over the center of the pelvis [from the face-on view], which is a relationship we see in basically every tour swing.”

The transition from backswing to downswing is where a lot of amateur swings go off the rails because of an instinct to create power with the arms or upper body. Neff says Curry does a good job of leading with his lower body, but then shifts his hands out slightly as he continues down, making his swing plane a little steeper than it was going back.

“It’s fine to be on the steep side,” Neff said, “as long as you’re playing a cut [which Curry does]. But most players who are steep, like Brooks Koepka, have the clubface more closed. Swinging steep and having to shut an open face can produce a pull-hook.”

ABOVE: GEARS detects a slight re-routing of the club to the outside—not ideal but not a killer.

Neff suggested that Curry work on keeping the clubhead more to the inside on the downswing; he calls it “lowering” the club, as opposed to shifting it outward. They look at split-screen comparisons, first with Rory McIlroy, then Jon Rahm, then Justin Rose. Each of the pros delivers the club to the ball on or under the backswing path; Curry is over it.

Neff is quick to point out that Curry does a lot of good things coming down: He turns his hips very freely and unhinges his wrists, getting a nice bowed position in his lead wrist, which means he’s reducing how much the clubface is open.

But another point of concern is Curry’s hip action. His pelvis drifts toward the ball as he swings into impact, a move GEARS hasn’t seen in many tour swings. Neff said tour pros tend to move their pelvis away from the ball. Moving toward the ball can cause heel shots or lead to a compensation, which can change the swing’s timing and cause inconsistency.

ABOVE: Curry shifts his hips toward the ball, a move rarely seen in tour-level swings.

“Amateurs tend to stand too far away from the ball, and then move toward it on the downswing,” Neff said. “Pros tend to stand more on top of the ball and move away from it. The answer here might be as simple as standing a little closer to the ball.”

The good news, according to Neff, is that Curry’s athletic instincts take over as he delivers the club to the ball. His lower body turns through fast, and he doesn’t sway much toward the target—two great moves for the fade pattern Curry prefers.

A few critical data points matched what Neff looks for in elite swings. First, every pro swing in the GEARS database has more body turn toward the target at impact than side bend away from it. This prevents the club from getting stuck behind the player coming down.

Second, Curry rotates his hips more forward at impact than he turned them away from the target going back. That’s another big one that Neff said all great players demonstrate, especially those who fade the ball. This hip rotation helps keep the arms from passing the body and flipping the clubface closed, which can cause that hook.

ABOVE: With a fast hip turn and not much body sway, Curry exhibits a classic fade pattern.

At impact, many of Curry’s numbers with the driver were tour level: His swing path was 0.5 degrees out to in (tour average: 1.1 degrees out to in); angle of attack 4.1 degrees upward (tour: 2.1 degrees up); clubface 1.4 degrees open (tour: 0.5 degrees open).

Not bad for a guy who spends a lot more time on the hardwood than the practice tee.

Neff said that Curry’s two big issues—his hands moving out on the downswing and his hips moving toward the ball—are almost certainly connected.

“When the hands go out, the pelvis tends to thrust toward the ball,” Neff said. “But Steph has such great hand-eye coordination and turns his body so well that he gets away with it—not every time, but a lot of the time.”

So why is it important to eliminate these moves?

“He’s relying too much on timing the swing with his hands,” Neff said. “If his body stalls at all through impact, the clubface will start closing fast, so he’ll fight that left miss. If he keeps his hands more to the inside coming down, his hips will be less likely to thrust, and he’ll be able to hit any shot he wants—not just a fade.”

Neff continues: “When you’re hitting driver off a tee, you naturally shallow out a little more, but with long clubs off the ground, a steep swing puts the path more leftward through impact—and you can get a big slice. Players start to sense that and try to actively close the face. Whatever the club, Steph needs to keep the clubhead more behind him on the downswing.”

Neff is bullish on Curry’s chances of getting to the next level, even competing as a pro. For perspective, Curry, at 36, is seven years younger than Tiger Woods was when he won his last major. Phil Mickelson was 33 when he won his first.

“He’s got the speed of a tour player right now [114 mph driver swing speed at impact versus 117 tour average],” Neff said. “And if he lowers the club earlier in the downswing a bit, he can easily get another 5 miles an hour, maybe 10. Plus, his body is going to age well, so that’s a huge advantage over other players approaching their 40s.”

The big question, of course, is what does Curry want?

“Right now, I want to win the Tahoe event every year—that”s my focus,” Curry said. “After basketball, I’ll have to reassess.”

Neff went a step further: “Swing-wise, he can get to tour level. Of course, it’s ultimately about scoring, and that’s short game. The pros know how to scratch out scores. Bottom line is, if Stephen Curry says he wants to do something, I’m not betting against him.”