Winter’s mighty grip plunges much of our world into a frozen pause. But even as plants go dormant, bears hibernate, and humans strive to get cozy, the planet itself keeps bustling along around us.

Strange things happen when frigid temperatures settle in for the long haul. Weird noises rise, freak snow showers fall, and odd formations lurch out of the ground during those frosty nights.

DON’T MISS: Annoying ways weather forces airlines to cancel your flight

Even as everything slows to a crawl when chilly weather arrives, things somehow seem noisier than ever during those fall and winter nights.

Highway traffic can sound deceptively close on a cold night. You might even hear things like train whistles and ship horns when temperatures take a dive.

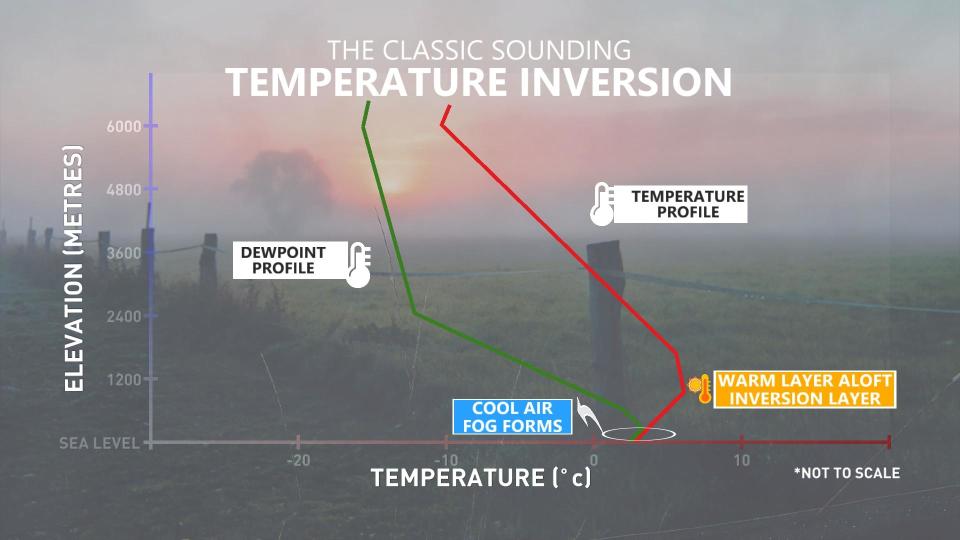

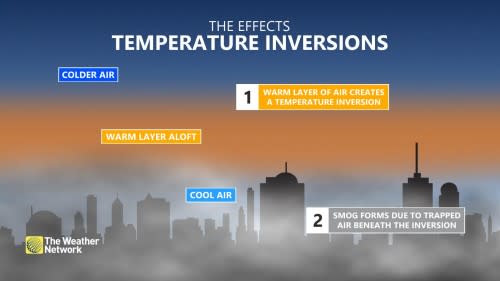

Temperature inversions are responsible for this apparent uptick in noise pollution when the weather turns colder.

An inversion occurs when a layer of warm air wedges atop a layer of cold air, leading to a difference in density that acts like a ceiling not far above the ground. Inversions are common on cold evenings when radiational cooling allows air near the ground to cool off much faster than air higher up in the atmosphere.

Under normal conditions, sound waves travelling in all directions through the atmosphere would dissipate with distance from the source—whether it’s traffic, machinery, or stadiums full of cheering fans.

But during a temperature inversion, that ceiling can force sound waves to bounce back toward the surface and extend their reach far beyond usual.

This effect—which is also a driving force behind evening fog and pollution problems—can allow loud noises to travel dozens of kilometres in extreme cases, making quite the racket on an otherwise calm night.

Summer’s strongest memories are often tied to smells. The scents of rain, freshly cut grass, and even the sharp tingle of a chlorinated pool leave an indelible impression.

But…so does hot garbage. Garbage cans and dumpsters are exceptionally odiferous during the summer, and it’s not entirely because all that waste is roasting in the midday sun.

Warm, humid air facilitates smells by allowing scent molecules to move more freely through the air while also heightening our nose’s ability to detect those smells lingering in the air.

Cold and dry weather, on the other hand, works against those factors to subdue both good and bad smells. The relative lack of scents makes those winter days smell crisp and clean—especially if there are heightened levels of ozone in the air, which leaves a distinctive smell and sensation in the nose.

The right conditions on a chilly day can lead to unexpected bouts of snow in unexpected locations. Billowing clouds of steam churned into the atmosphere from nuclear power plants and some factories can lead to localized snow showers downwind from these large facilities.

Steam rising from a nuclear power plant in Belgium. (UNSPLASH)

RELATED: Nuclear snow? Seven strange ways humans can change the weather

Hot steam rising into very cold air can trigger convection, much in the same way we see lake-effect snow during the fall and early winter months. This setup usually only results in a big, puffy cloud over the plant, but these cumulus clouds can go on to produce snow if there’s enough rising air and moisture present.

The resulting steam-effect snow bands can be so tiny that they only cover a couple of neighbourhoods. While this bizarre phenomenon is largely harmless, suddenly slick roads on an otherwise clear day can lead to dangerous travel.

If you’ve ever taken a look at the ground after a hard freeze, you may have seen needle ice poking out of the ground like an upside-down icicle.

It’s not uncommon for rain to fall just a few hours before a hard freeze. If there’s still plenty of liquid water in the ground as temperatures plunge below zero, that water will expand as it cools down and begins to freeze.

Needle ice forms in the grass near Killarney, Ontario, in November 2020. (Submitted by Meaghan Gouchie)

Not all of the water freezes at once. Ice forms closest to the surface first, slowly working its way down. If this process occurs slowly enough in tiny cracks and holes in the soil, expanding water will push that ice above the soil as it freezes. Over several hours, this gradual process can leave a tiny, fragile needle of ice poking up out of the soil.

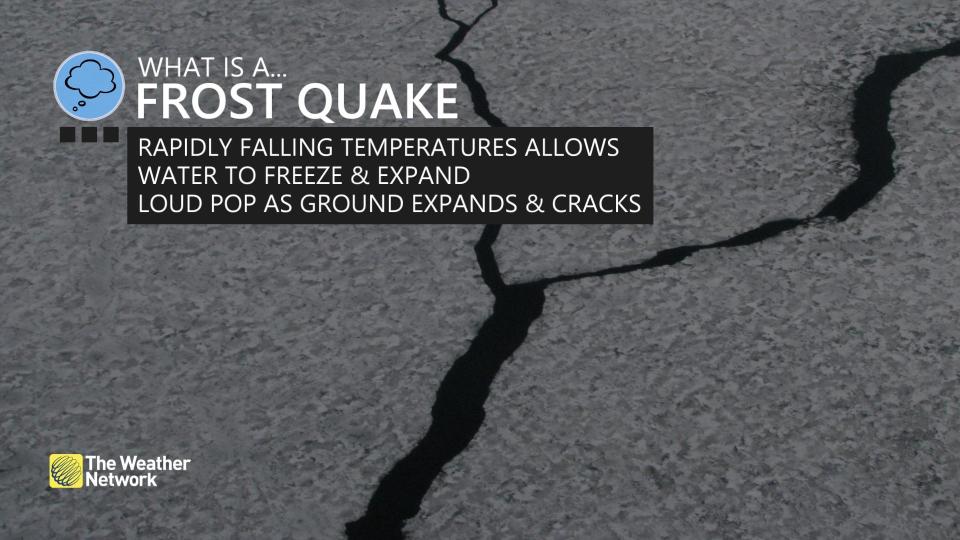

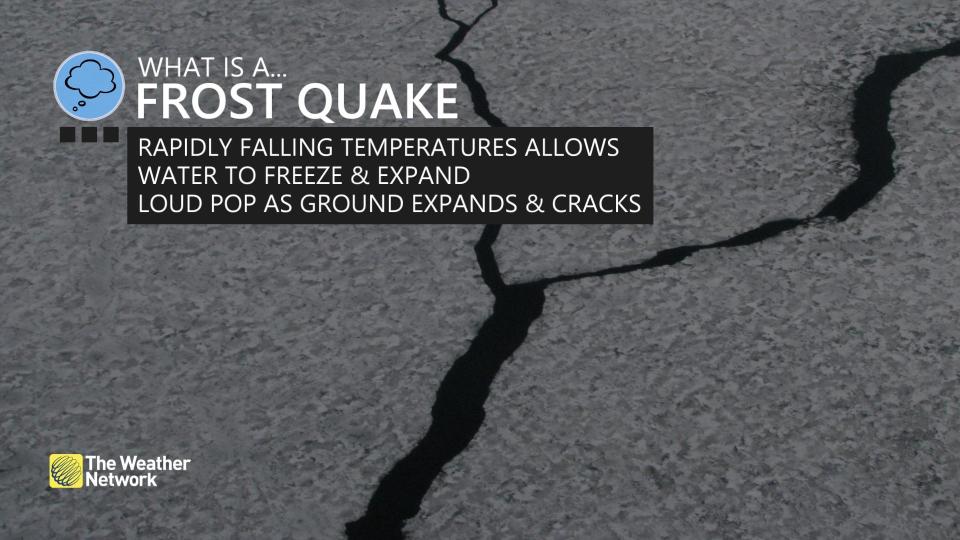

There are sudden cooldowns—and then there are flash freezes. Some cold fronts are so abrupt that temperatures can plunge dozens of degrees in a short period of time.

During warmer times, water dozens of metres beneath the surface can seep into cracks in the bedrock. That water freezes in a hurry as temperatures fall to brutally cold levels, and the force of the expanding ice cracks the bedrock.

This ice-induced fracture is sometimes so intense that it creates a loud boom and rattles communities directly above the rupture, a phenomenon known as a frost quake. The explosive sound is startling enough, but the shock can be intense enough that it registers as a small earthquake on seismometers.

Header image of inversion fog at B.C.’s Panorama Mountain Resort submitted by Khalid Aziz.