The ovaries are involved in far more than just reproduction. The two oval-shaped glands that float on either side of the uterus don’t just produce and release eggs, they also pump out hormones that help keep a person’s heart, bones, brain, and immune system healthy as they age.

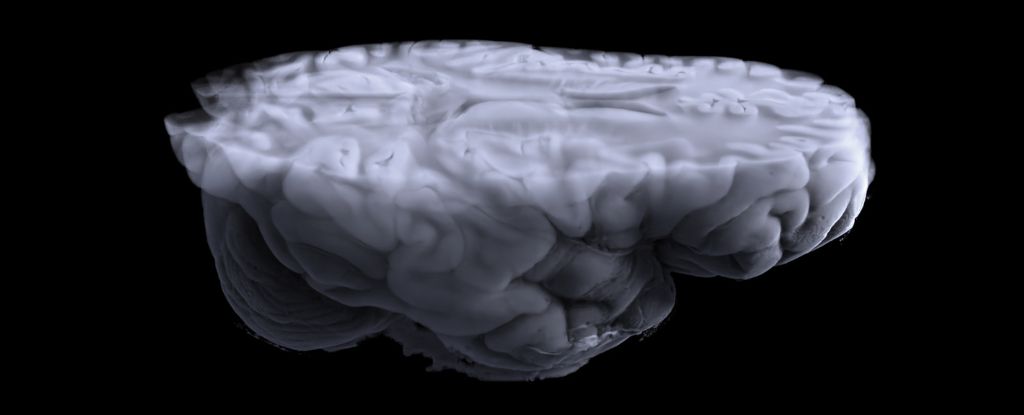

A new brain imaging study has scientists concerned that the surgical removal of both ovaries can have overlooked health consequences in the long run.

The analysis included data from more than 1,000 females over the age of 50 in the US. Participants who had both ovaries removed before the age of 40 showed reduced white matter in several parts of their brain compared to 907 females under the age of 50 who had not undergone the same procedure.

Participants who had both ovaries removed after age 40 also showed reduced white matter integrity, but significantly less so than those who underwent the surgery younger.

The observed changes resembled vascular brain disease more closely than Alzheimer’s, the researchers note, but it’s also true that these are “early, preclinical features of [Alzheimer’s disease] pathology.”

Recent research has found that patients who’ve had both of their ovaries removed before they hit menopause face a higher risk of cognitive impairment and dementia later in life. But this is one of the first studies to try and figure out why.

To date, male brains have been the focus of the vast majority of neurological studies. Of all published brain imaging papers out there, less than 0.5 percent consider and explore the way hormones – including those produced by the gonads – can impact brain health and development.

In general, male brains possess greater white volume matter compared to female brains. Some scientists suspect this is due to differences in how sex hormones, produced by the testes and ovaries, impact the developing brain.

While testosterone is often thought of as a male hormone, it is also produced by the ovaries, and it plays a critical role in the female body. The hormone is also linked to white matter integrity in the brain.

If the ovaries are taken out of the body before menopause, the sudden loss of testosterone could have negative effects on the brain’s development.

In the current brain imaging analysis, participants who had both their ovaries removed before age 40 commonly took estrogen to replace what their sex gonads once made. But this hormone replacement therapy had no impact on their white matter integrity.

“[I]t may be hypothesized that the explanation for our results is in part due to loss of testosterone,” the team of researchers suggests.

“Additional studies to replicate this finding are clearly needed.”

Many unanswered questions still exist to this day about what role the ovaries play in the lifelong health of female-bodied individuals and what happens when they are removed.

For years now, scientists have debated the costs of removing the ovaries for benign conditions, and if so, at what age it is safest to do so.

In cases of cancer, it’s vital that the ovaries are excised to save the patient, but bilateral oophorectomies are also commonly used to treat endometriosis, ovarian cysts, and non-cancerous fibroids.

In the US, just over half of all people undergoing a hysterectomy have both of their ovaries removed as well, and more than a third of that group are under the age of 44.

In light of recent evidence, some experts argue that the risks and benefits of removing both ovaries at a young age are not being weighed appropriately by surgeons or patients. For children and adolescents, removal of both ovaries for benign conditions may be ‘unnecessary‘ and come with lifelong risks.

If both ovaries are removed during a person’s reproductive years, the body can enter early menopause, and this increases the risk of severe chronic health conditions that include bone density loss, impaired sexual health, cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, sleep apnea, and arthritis.

There are numerous reasons the ovaries should be spared when possible. Protecting the brain from possible harm is just one of them.

The study was published in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.