Every week, police in northeastern Ontario respond to more than 100 calls related to intimate partner violence (IPV).

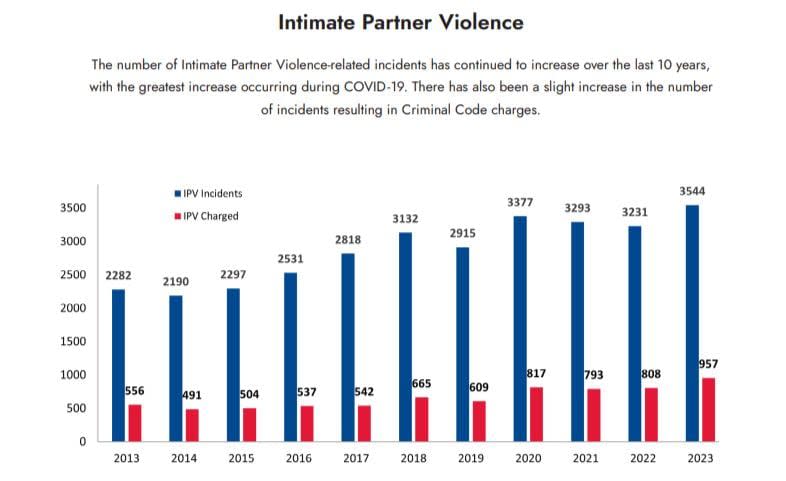

In Greater Sudbury, the region’s largest city, police responded to 3,544 IPV calls last year and laid 957 charges.

“We’ve seen an increase in the number reported, certainly since COVID,” said Greater Sudbury police Det. Sgt. Lee Rinaldi, who oversees the service’s major sex crimes division.

Since 2020, the police service has consistently responded to more than 3,000 calls a year related to IPV.

Rinaldi said part of the reason police answered to more IPV cases during the pandemic is people were home for longer periods of time, which led to more cases of domestic violence.

Chart shows intimate partner violence incidents and charges in the Greater Sudbury Police Service’s jurisdiction over a 10-year period. (Greater Sudbury Police Service)

While numbers remain high this year, he said what police calls Priority 1 and 2 calls are down, while lower-priority calls are up.

The high-priority calls are when a person is in immediate danger from an intimate partner. They may have been recently attacked or their aggressor is nearby.

The lower-priority calls are when the person is not in immediate danger, but could be reporting ongoing harassment, such as threatening calls or messages.

Rinaldi said there’s been an increase in charges this year for non-bail compliance, for people who have faced criminal charges related to IPV in the past.

“So because we have increased our bail compliance and focus on bail compliance … we’ve seen an increase in the number of those types of calls, which really does bring our numbers up considerably,” Rinaldi said.

IPV declared an epidemic

Following several high-profile cases, including a murder-suicide in the northern Ontario city of Sault Ste. Marie last year in which three children and two adults were killed, hundreds of communities across the province have declared IPV an epidemic.

The province has not yet followed suit, but a private member’s bill to recognize IPV as an epidemic across Ontario passed second reading in April.

Rinaldi said greater societal awareness of IPV has meant police have changed their approach to how they investigate domestic crimes.

“There’s a cycle of violence that includes an imbalance of power within a relationship where there’s manipulation inflicted on other individual, which could really run the spectrum — everything from physical violence against an individual, to using forms of manipulation, you know, certainly threatening to harm the other person, threatening to harm the other person’s family, threatening to harm themselves by way of suicide.”

Carol Fournier was killed by her ex-partner in Sudbury in November 2023. Fournier was on a safety plan at the time of her death to due concerns around intimate partner violence. (Greater Sudbury Police Service)

Rinaldi said that in some cases, property disputes between partners can also fall under the IPV umbrella.

In North Bay, around 120 kilometres east of Sudbury, police responded to 1,517 IPV-related calls in 2022 (the most recent year with available statistics).

That year, North Bay police charged 311 men and 119 women with crimes, including assault, criminal harassment, sexual assault and breach of probation, following those calls.

In Sault Ste. Marie, where the deaths of Angie Sweeney and three children to domestic violence put a national spotlight on IPV, police have consistently responded to more than 1,300 IPV-related calls over the last three years.

Last year, police in Sault Ste. Marie charged 238 men and 57 women for IPV-related crimes.

More awareness

Erica Gertz, executive director of Sudbury and Area Victim Services, said her organization sees between 30 and 60 people a week who have been affected by IPV.

“I think there’s a lot of community services out there that are helping, and therefore maybe more people are coming forward,” she said. “They feel safer to report.”

When Sudbury and Area Victim Services works with a person affected by IPV, Gertz said, they start by assessing the person’s needs and then work with other organizations to help them meet those needs.

That can include moving them to a safe space or even a new community.

“There are some agencies in Sudbury that have taken the lead on that and we do support, you know, that there needs to be more safe places for women to go and more advocacy for women that find themselves in intimate partner violence or abusive relationships,” Gertz said.