Proof point: Lower-wage industries in Canada with more younger workers have been disproportionately impacted by the recent softening in labour demand, while higher-wage sectors have emerged as clear winners in a jobs market redefined by the pandemic.

One silver lining in the Canadian labour market after the pandemic lockdowns was the strong demand for professional, scientific, and technical workers that allowed many well-educated and likely underutilized workers in the hospitality sector to make the jump to higher-paid work.

Jobs in the professional services sector pay more than a third above the Canadian average and are more likely to be performed remotely such as legal services, accounting, engineering, design, advertising and scientific research and development.

Hiring in hospitality sectors sharply lagged, because there simply weren’t enough workers available to fill jobs. Surging demand in higher-wage sectors meant fewer workers were available for jobs that paid less.

But, that backdrop has now shifted. Lower wage industries such as accommodation and food services are still underperforming higher wage industries, but not because of a shortage of labour—there’s much softer hiring demand.

Over the past two years, rising interest rates have significantly cut into household purchasing power and lowered consumer demand. By our count, real spending on retail, restaurants and bars has each contracted by about 2% per person a year over the last two years.

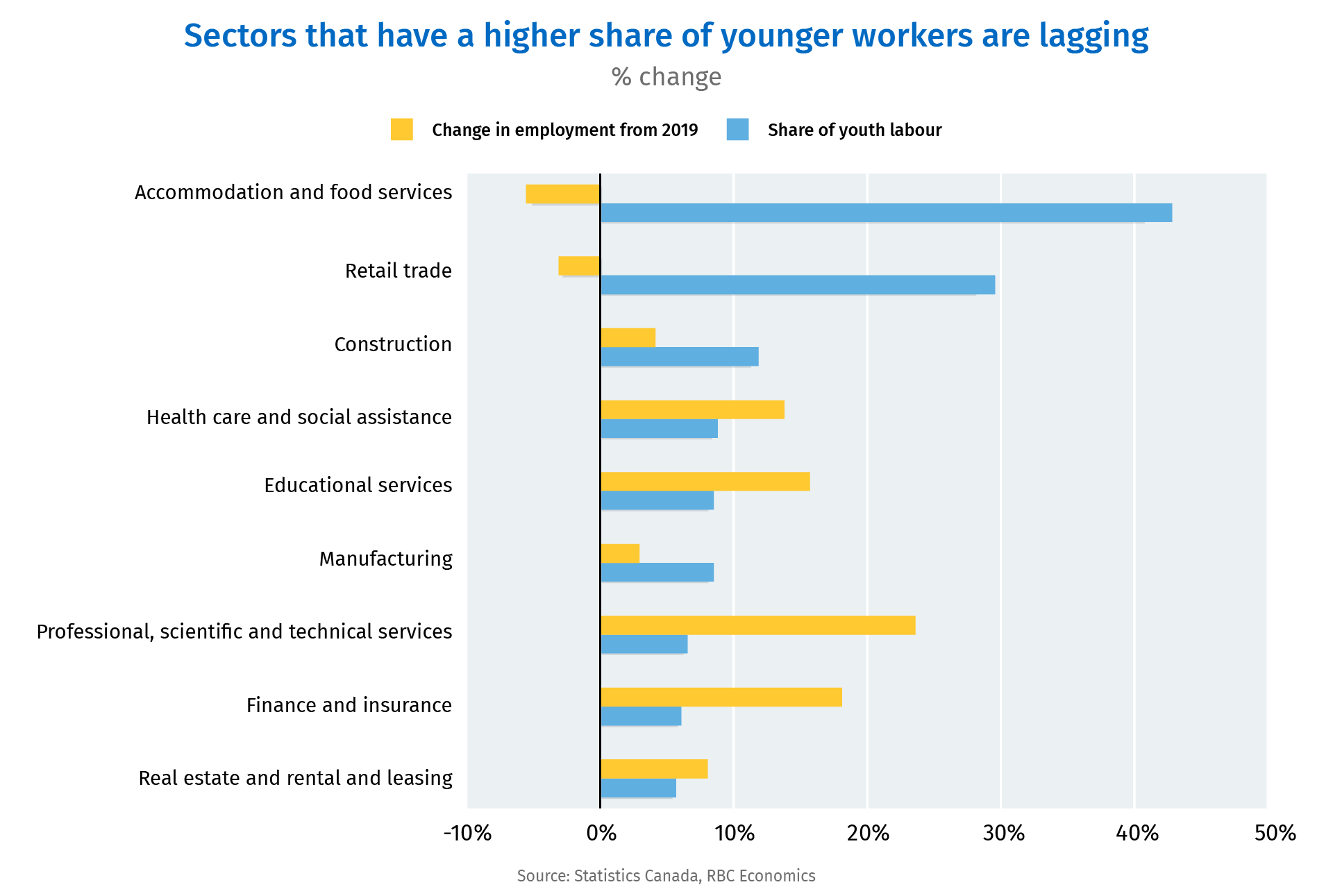

As a result, business hiring has significantly softened with job openings plunging below pre-pandemic levels. Retail, accommodation and food services combined lost more than 100,000 jobs since the summer of 2023, leaving employment in these sectors in October 6% below levels before the pandemic.

In the meantime, employment in professional, scientific, and technical services has continued to grow, with employment now around 23% above early 2020 levels.

The larger pullback in employment among retail, accommodation and food services means much of the slowing in the labour market has impacted workers who tend to earn lower wages, and are often, younger.

By our count, around 30% of workers in retail and 40% of workers in accommodation and food services are aged between 15 and 24. These sectors have the highest share of youth employment—drastically higher than 13% across all sectors.

That explains why a disproportionately large share, close to 40% of the rise in the unemployment rate in Canada since the lows after the pandemic has come from workers aged 15 to 24. A big driver of this has been recent graduates being unable to find work.

The good news for them is the Bank of Canada is now in an interest rate-cutting cycle. We expect broader consumer demand will start to look better. The bad news is monetary policy works with a lag. That means the recovery in hiring demand will come slowly. In the near term, it could still take younger workers longer than usual to find a balanced footing in the labour market.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic analysis and is responsible for projecting key indicators including GDP, employment and inflation for Canada and the US.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.