A recent study has revealed significant insights into the early brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease, focusing on volume loss in key brain regions. The researchers found that volume loss in the basal forebrain and hippocampus is more pronounced in individuals with high levels of amyloid-beta, a protein linked to Alzheimer’s, even before cognitive symptoms become apparent. The effect of amyloid-beta concentration on the pace of brain shrinkage (volume loss) varied between brain regions. The study was published in the Neurobiology of Aging.

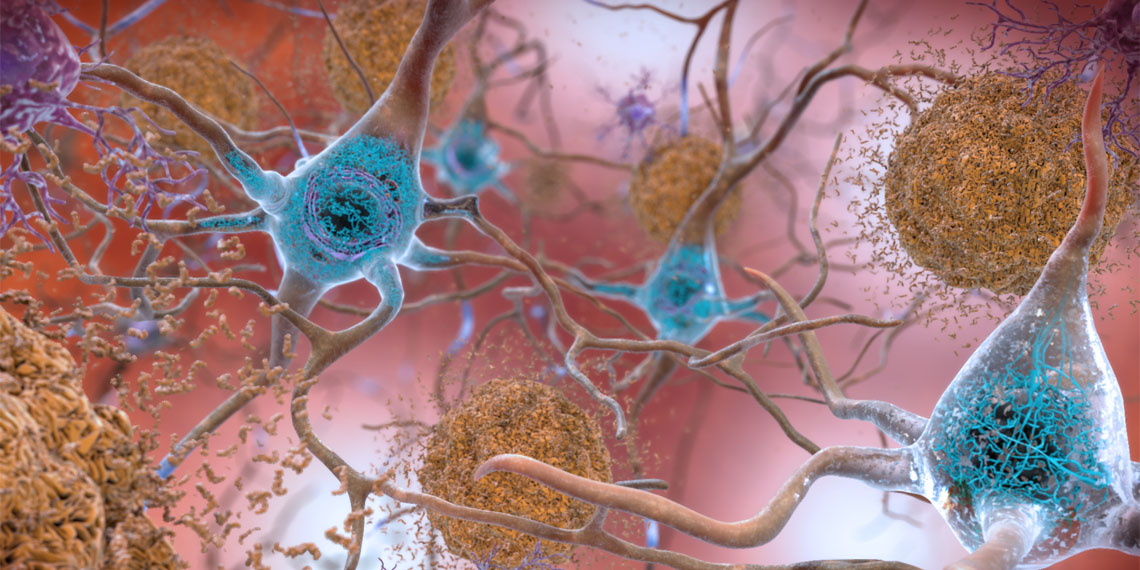

Amyloid-beta is a peptide that accumulates in the brain and forms plaques, disrupting communication between neurons and leading to their death. This peptide, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, contributes to the progressive decline in cognitive functions. Over time, the accumulation of amyloid-beta impairs neurons’ ability to form new connections, crucial for learning and memory.

This accumulation can also impair synaptic plasticity, the ability of neurons to form new connections. Over time, the loss of neurons becomes widespread, leading to a decrease in the volume of neuronal matter in affected brain regions, resulting in brain shrinkage.

Study author Ying Xia and her colleagues wanted to investigate the nature and magnitude of volume loss in the basal forebrain and hippocampus regions of older individuals with and without Alzheimer’s disease. As the brain naturally loses volume with age, leading to overall cognitive decline, the researchers aimed to determine if the pace of this decline is associated with the level of amyloid-beta in the brain.

Data for this study came from 516 individuals aged 60 years or more participating in the Australian Imaging, Biomarker and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. At the start of the study, 40 of these individuals had Alzheimer’s disease, 62 had mild cognitive impairment, and 414 were without cognitive impairments.

At the start of the study, participants underwent positron emission tomography (PET) imaging to assess amyloid-beta levels, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess brain volumes, and completed cognitive assessments. They were followed for up to 14 years, with an average follow-up of 5 years. During this period, participants completed at least one more MRI, with 61% completing three or more MRIs, while the remaining participants completed two.

Based on their condition at the start of the study, participants were categorized as either having or not having cognitive impairment and as either having high or low levels of amyloid-beta plaques in their brains. At the start of the study, 56% of participants had neither cognitive impairments nor high amyloid-beta levels. Twenty percent had high amyloid-beta levels but no cognitive impairment. Seventeen percent had both cognitive impairment and high amyloid-beta levels, while 8% had cognitive impairments with low amyloid-beta levels.

Individuals who were cognitively impaired and those with high amyloid-beta levels tended to have lower volumes of the basal forebrain and the hippocampus at the start of the study. Over time, results showed that both the basal forebrain and hippocampus in participants with high amyloid-beta levels lost volume faster compared to those with low amyloid-beta levels.

“These findings strongly support the early and substantial vulnerability of the BF [basal forebrain region] and further reveal the distinctive degeneration of BF subregions in normal aging and AD [Alzheimer’s disease],” the study authors concluded.

The study sheds light on the links between amyloid-beta levels and the pace of brain shrinkage with aging. However, the study authors note that participants in this study tended to be better educated than the general population, had high scores on cognitive tests, and had few additional medical conditions. Results might differ if the study were conducted on individuals more representative of the general population.

The paper, “Longitudinal trajectories of basal forebrain volume in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease,” was authored by Ying Xia, Paul Maruff, Vincent Doré, Pierrick Bourgeat, Simon M. Laws, Christopher Fowler, Stephanie R. Rainey-Smith, Ralph N. Martins, Victor L. Villemagne, Christopher C. Rowe, Colin L. Masters, Elizabeth J. Coulson, and Jurgen Fripp.