On Monday, November 11, Canadians will observe Remembrance Day, 106 years after the armistice that ended the First World War.

That conflict took a terrible toll on the youth of the nation, but it was a crucial stage of Canada coming into its own. And, appropriately for a country to attuned to the weather, Canadian troops proved to be experts at fighting in at-times brutal conditions, during the war and in other conflicts throughout history.

Here are six major Canadian battles shaped by the weather.

If you’re looking for one battle that sums up almost the whole experience of the First World War, it’s the Third Battle of Ypres. Or, as we know it, Passchendaele.

Source: William Rider-Rider/Wikimedia Commons

SEE ALSO: The unbearable weather conditions of First World War

Thousands of lives were lost for minimal territorial gain, among them 15,000 Canadians killed or wounded in one of the battles that helped forge our nation’s identity.

And as for the weather, it was so dismal it has become a part of the story.

The worst rains in 30 years turned the already bombed-out landscape into a nightmarish morass. Schoolchildren learn the stories of men and horses sinking and drowning in the mud. The quagmire clogged rifles and bogged down tanks. The downpours flooded foxholes and craters alike, robbing the advancing Canadians and British of valuable shelter, even as they pressed forward in waist-deep floodwaters.

Still, they made it, securing the area by November 10, including the bombed-out ruins of Passchendaele itself.

To this day the argument rages over whether the whole thing was worth it, even as the courage of Canadian troops, in one of the first real tests of their mettle, continues to be celebrated.

When Allied boots hit the ground on the beaches of Normandy, it was the beginning of the end for Germany’s stranglehold on Europe.

Source: Library and Archives Canada/Wikimedia Commons

At the time, though, it must have seemed like a big gamble. As it was, the June 6 landing date was already 24 hours later than planned, due to lousy weather.

That same weather limited the amount of damage aerial and coastal bombardment could do against the Nazi’s seaside defences, so when Canadian troops set sail in their landing craft for Juno Beach, they would potentially face the defenders at full strength.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Making matters even worse were choppy waters, with waves more than two metres high, that made it hard to land the tanks the Canadians would need to meet their objectives.

Still, the 15,000 men of the landing party made it to the beach, and faced some of the toughest resistance of all the Allied forces participating in the assault.

Several hundred of the invaders at Juno were killed – but not only did they take the beach, Canadian units penetrated deeper inland than any of their British and American comrades, making a good head start on the eventual liberation of the continent.

Although German forces never had a realistic chance of turning back the Allies once they’d made it past the beaches of Normandy, at the time, it seemed like Hitler’s counteroffensive in the Ardennes might do the trick.

The operation, launched in December 1944, was aimed at driving a wedge between, and surrounding, Allied forces, including the First Canadian Parachute Battalion.

Source: U.S. Army/Wikimedia Commons

Its German planners were specifically banking on the weather coming to their aid. Low fog and cloud cover neutralized Allied air superiority, and German disinformation campaigns had a good degree of success.

The Germans, in the meantime, expected the ground to be frozen solid, ideal for the kind of tank warfare that had served them well in the initial conquest of Europe.

Despite their great initial successes, the counteroffensive faltered when the weather cleared, and the Germans ran into serious fuel shortages that put a big damper on their tank tactics.

Source: U.S. Army/Wikimedia Commons

While it was mainly American forces that felt the brunt of this last gasp by the Germans, the First Canadian Parachute Battalion division played its part, and is today credited with venturing deeper into enemy territory than any other Canadian force.

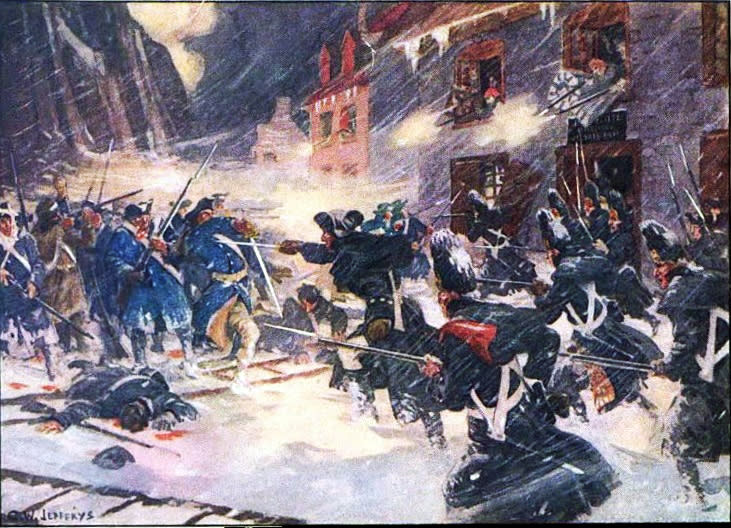

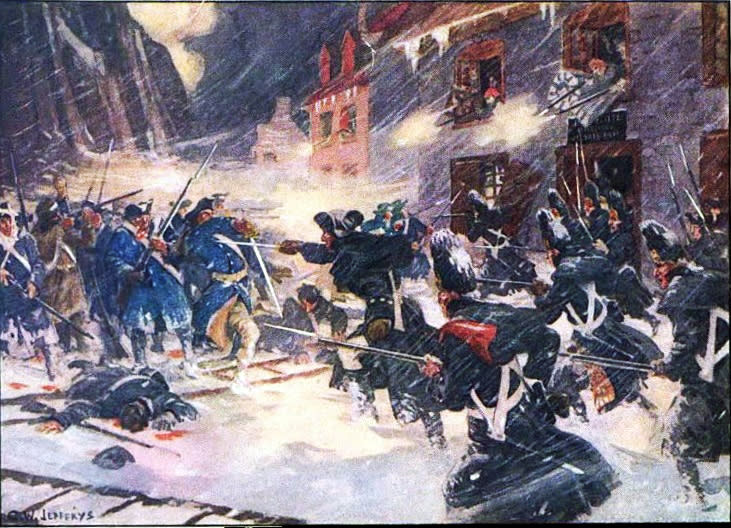

We’re going to flash back to a battle that defined the nation even before Canada as we know it was born.

For the Americans, in the early stages of the American Revolution, this could not have been a worse fight to pick.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

In an effort to knock out the British base in Canada, an American force set out for Quebec City, hoping that the Quebecois, conquered by the British less than two decades prior, would side with them. However, they took a wilderness route through what is now Maine, and many died of starvation before even reaching the walls of Quebec.

Reinforcements arrived, but even so, it was a relatively rag-tag force, ill-equipped, exhausted and far from home at the gates of a heavily fortified city packed with a numerically superior garrison that included artillery.

The attackers decided to take their chances, attacking the city at 4 a.m. on the last day of the year, in the middle of a blinding snowstorm. It was hoped that the terrible weather conditions would give the invaders cover, but those same conditions had badly sapped their strength.

Source: John Trumbull/Wikimedia Commons

The assault was a dismal failure (one of the Americans’ two generals was killed in one of the first volleys), and around a third of the attacking force was killed, captured or wounded.

The Americans tried to continue the siege, but were forced to retreat when a British fleet arrived carrying reinforcements. They were soon driven from Quebec altogether, and the Americans would not try to invade Canada again in force until the War of 1812.

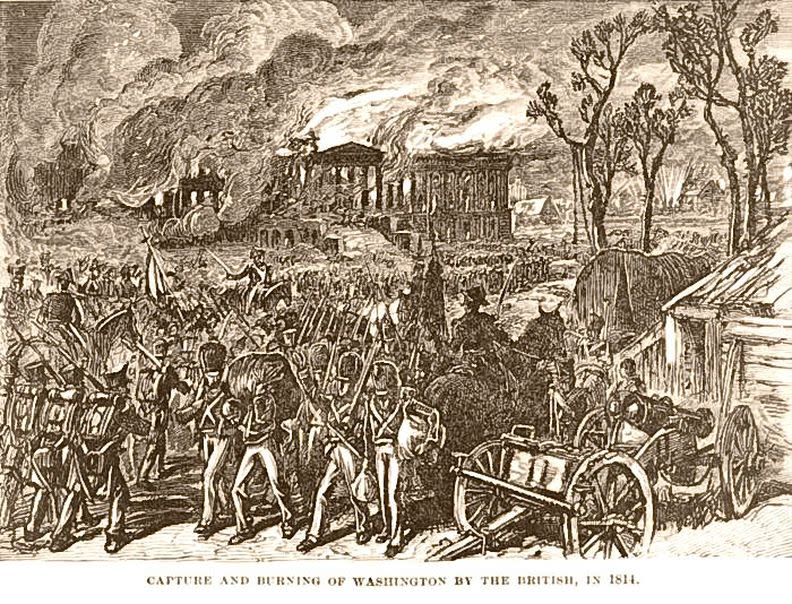

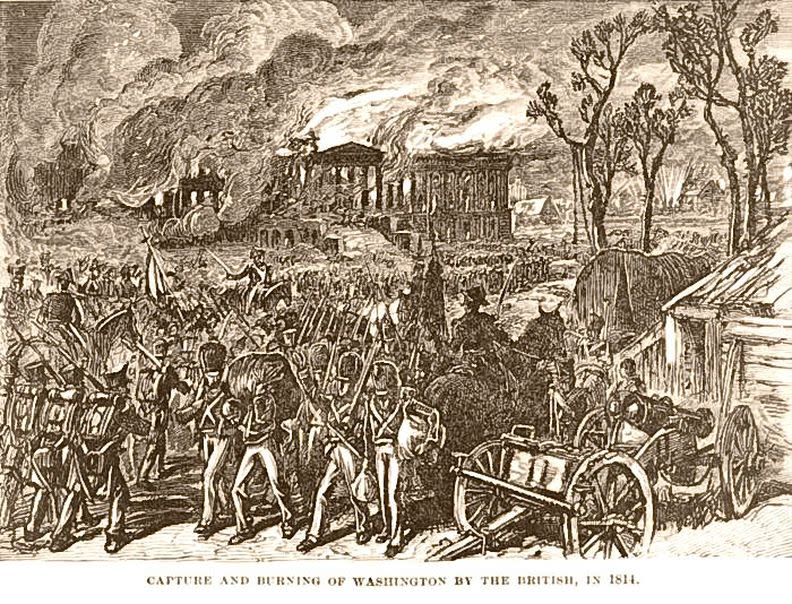

Few Canadian troops were involved in this famous and popular (among Canadians at least) episode of the War of 1812, but we’re including it because it was in large part sparked by events up north.

Source: Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons.

The Americans had succeeded in sacking York, in what is now Toronto, burning both public and private buildings. The British, who had already repulsed American land invasions from Ontario, were spoiling for some payback, in the form of an attack of the United States’ then-tiny and strategically insignificant capital of Washington.

After landing, the British routed the American defenders and waltzed into Washington, burning the White House and other public buildings.

Then the tornadoes came.

We don’t know for sure how many there are. This source says “one or two,” while this one claims three that may have been the same one sighted different times.

Regardless, the storms were unlike any the occupying force had ever encountered, lifting homes off foundations and tossing men and cannons alike. Accompanying the storm was a driving rain that doused the fires set by the British. Thirty Americans were killed, and an unknown number of Britons.

By the time it cleared, they’d had enough, embarked on their ships and left. The occupation of Washington had lasted only 26 hours.

We’re betting you didn’t know about this odd episode of our military history, so here goes: At the end of the First World War, Canada invaded Russia.

Source: Library and Archives Canada/Wikimedia Commons.

Yes, really. It happened. Canada loaded more than 4,000 men onto ships in Vancouver and sent them to occupy Vladivostok, the largest town on Russia’s Pacific coast. In wintertime.

The reasons for this were a huge political jumble, a mixture of opening up trade opportunities and wanting to nip the Russian Revolution, led by the Bolsheviks, in the bud (Canada was one of several nations to back anti-Bolshevik forces, part of what historians call the Russian Civil War).

The small force almost never left Vladivostok, mostly patrolling and performing military drill in and out of the city. This source recounts the kind of boredom the troops faced, complete with games and Russian language classes – all while in the midst of the legendarily frigid Siberian winter.

Source: Library and Archives Canada/Wikimedia Commons.

A handful of troops did venture upland to link up with British forces in Omsk, but for the most part, the Canadians saw little combat as they waited out the domestically unpopular mission.

Still, due to a combination of growing insurgent operations and disease, 14 Canadians lost their lives far, far from home, and are buried in Vladivostok (five more were buried at sea).

A strange episode in Canada’s military history, but one that should not be forgotten.