“Ozempic doesn’t have to be forever.”

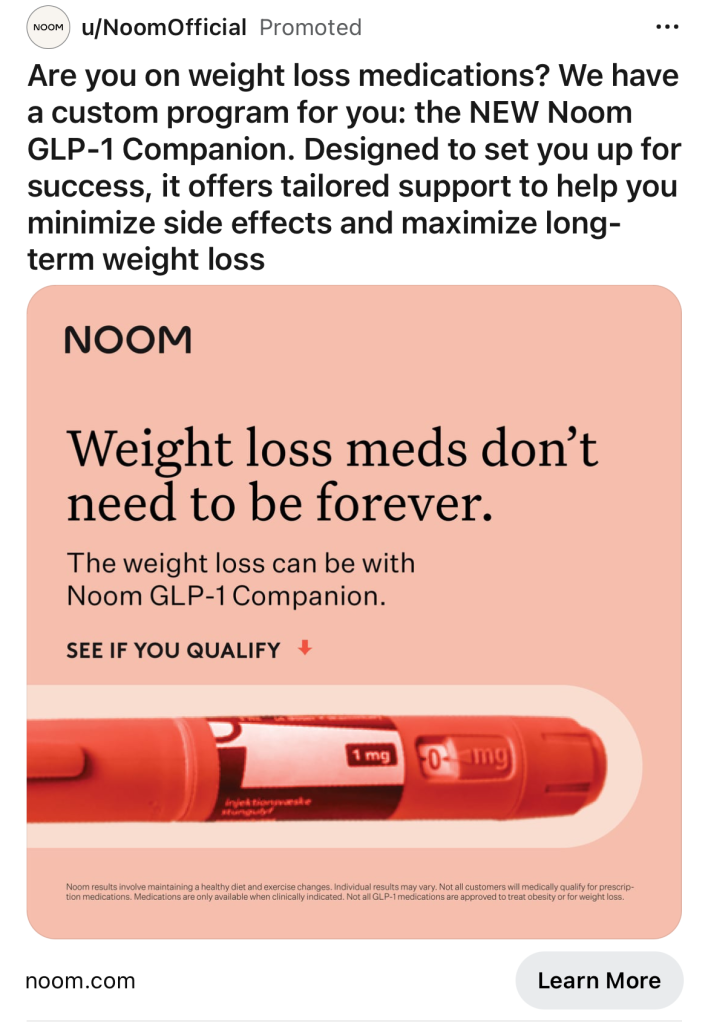

It’s a line that may appear on your social media feeds if you’ve googled how to lose weight, or read up on Hollywood’s latest miracle drug: Ozempic. The pink ad, posted as part of a campaign on Reddit, Instagram, and Facebook in recent months by the $3.7 billion weight-loss startup Noom, shows the drug’s blue syringe pen moving back and forth below a timeline that doesn’t extend beyond a year.

What the ad promises is nothing short of the Holy Grail of the $90 billion U.S. diet industry, the cure that Americans, especially American women, have sought for generations and are willing to pay dearly for: a new, more slender you, hassle-free. Quick weight loss, then a return to your familiar life—thinner, healthier, and happier. It’s no wonder that, since this new class of appetite-curbing GLP-1 medications, including Ozempic, Wegovy, and Zepbound, burst into public consciousness, nearly $1 billion of venture capital dollars have been injected into the growing sector of weight-loss companies, which is now awash with startups prescribing the drugs, according to PitchBook data from the last year and a half.

It’s true that these medicines appear to be startlingly effective for weight loss, a game changer for many people with obesity. But the second part of what some startups prescribing these medications promise—the “doesn’t have to be forever” part, or the notion that these drugs can “reset” your metabolism—is far more contentious. As the drug manufacturers Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly have made exceedingly clear, these medicines are intended as long-term commitments, like medication for high blood pressure. They are not meant to be taken temporarily.

Indeed, seven doctors who spoke with Fortune say the preponderance of medical trials so far show that generally, people who stop taking the drugs regain most of the weight they’ve lost within about a year. Fortune also spoke with half a dozen people who had stopped taking GLP-1 medications—all of whom said they started regaining the weight they had lost when they stopped taking the medications and their food cravings returned.

“There is no such thing as a ‘metabolic reset,’” says Dr. Angela Fitch, chief medical officer of Knownwell, a primary care and obesity medicine provider, and past president of the Obesity Medicine Association. Dr. Caroline Apovian, the co-director of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, agrees: “The studies show over and over and over again,” Apovian says, that if you stop taking the medications, “you will regain the weight back.”

Noom isn’t the only startup to market GLP-1s as temporary treatments that offer long-term effects. Calibrate, which began prescribing anti-obesity medications in 2020 as part of a weight loss program, prominently describes the drugs as a “temporary aid to improve your metabolic health.” In Denmark, a venture-backed startup, Embla, says on its website that it offers GLP-1s “always with the clear aim of a healthy transition off medication once you’ve reached your goals.” (Other companies, including the weight-loss giant WeightWatchers and more recent incumbents such as Ro, have begun dabbling in GLP-1 medications, too, though they are clear in their messaging that these drugs are meant to be taken long-term.)

A spokeswoman for Noom frames the issue as partly one of customer demand: When asked about the company’s marketing of Ozempic as a drug to take for a limited time, she emphasized that most patients don’t want to stay on the medications forever, noting that research showing that “68% of people stop taking the GLP-1 by month 12 suggests a reticence to a forever medication by many. It would be difficult to stress this point enough.”

While GLP-1 medications have been on the market to treat type 2 diabetes for decades, it is only recently that some have been adapted, and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as a treatment for weight loss—so the research on these drugs, and their long-term side effects and risks, is still nascent. And the question of whether people can maintain weight loss after going off GLP-1 medications is an ongoing area of study: The science is far from settled.

Noom, Calibrate, and Embla say there is preliminary data to support their contention that many people can maintain weight loss through exercise and diet after stopping the medications (though some of the doctors Fortune spoke with were skeptical of those studies). Anecdotally, there are examples of people who have managed to do so by sticking to strict diets and exercise regimens.

But it’s clear that not everyone can maintain such an intensive regimen—that’s part of the problem the weight-loss drugs are meant to solve. And with so little definitive data on the long-term health effects of taking—or stopping—this new class of drugs, weight-loss companies’ suggestion that the drugs can be taken temporarily is worrying, says Ragen Chastain, a researcher, board-certified patient advocate, and author of a newsletter that explores weight science. “They are making long-term promises based on short-term data,” she says, pointing out that even that data “still doesn’t necessarily actually support the claims that they’re making.”

There is no such thing as a ‘metabolic reset.’

—Dr. Angela Fitch, chief medical officer of Knownwell

For now, the medication-aided weight loss industry is still in its gold rush era, and patients—some of whom have struggled for their whole lives with their weight and haven’t been able to lose it with diet or exercise—are dropping pounds while taking the drugs.

But as Noom points out, it appears that most people taking these new medications, whether or not they use a weight-loss company to prescribe them, are eventually going off their medications, whether it’s because of the expense, shortages, side effects, or an aversion to the idea of staying on a medicine perpetually. Two-thirds of patients stopped taking the drugs within a year of starting them, according to one recent analysis of insurance claims.

Will these weight-loss drug quitters be able to keep the weight off, or yo-yo back, as with many other crash diets that have come before? That’s likely to become an increasingly urgent question in the months and years ahead. But that uncertainty hasn’t stopped some companies from reassuring customers that they can take, and stop, the drugs at will.

The competitive startup world can be a strange place for a new medication to proliferate, Chastain points out, because of the pressure from venture capital investors to scale. “That culture of ‘move fast and break things’—when applied to people, and people become the ‘thing’—is really dangerous,” she says, adding later: “There is a lot of potential for harm to be done here when startup culture meets health care.”

It’s not hard to understand why investors see the GLP-1 market as one prime for scale. Wall Street analysts expect between $33 billion and $100 billion in annual revenue from anti-obesity medications in the next six years, according to J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, the primary pharmaceutical companies making the medications, have skyrocketed in market value, and Novo Nordisk’s has superseded the gross domestic product of the country where it’s based, Denmark. Everyone from your best friend to your favorite movie star to Elon Musk seems to be talking about slimming down with semaglutide, the active ingredient in both Ozempic and Wegovy; tirzepatide, in the form of Mounjaro or Zepbound; or liraglutide, in Saxenda.

And startups that peddle these medications as part of a weight-loss program are reeling in capital. Ro, for example, raised more than $150 million in January 2022 at a $7 billion valuation. Calibrate has raised over $160 million. A dozen or so other startups have entered the space, offering telemedicine appointments and GLP-1 prescriptions—including Measured, Nextmed, Mochi Health, Accomplish Health, Sunrise, and the buzzy direct-to-consumer company Hims & Hers. Venture capital firms including Tiger Global, General Catalyst, Founders Fund, and Silver Lake Partners have poured hundreds of millions into these companies.

It’s easy to see why messaging suggesting that short-term use of GLP-1s is possible would appeal to customers, given the cessation rates. Doctors tell Fortune that some patients don’t like the idea of having to take a drug for the rest of their lives. And many experience uncomfortable side effects—nausea, serious fatigue, or not being able to keep food down. In some cases, people don’t think they need the medication any longer because they have met their goals and feel they’re doing well—eating less, choosing healthier options, and exercising.

The drugs are also expensive: GLP-1 medications typically cost between $930 and $1,350 a month without insurance, and research shows the majority of people on them are paying at least part of that cost, if not all, themselves, particularly as some insurance plans are becoming stricter when it comes to what they’ll pay for.

“I actually wanted to go back on [Ozempic], and I’ve been trying since January, but my insurance won’t approve any GLP-1s,” says Ri Sharma, a 24-year-old marketing strategist who lost 61 pounds while taking Ozempic in 2023. Sharma went off the drug after reaching her goal weight in November last year, but her appetite resurfaced in late February, and she has regained about half of it back. “I’m just eating a lot more than I used to,” she says.

The companies that manufacture GLP-1s have gone to lengths to assert that these medicines are not meant to be taken only temporarily. “Obesity is a chronic disease and, just like any other chronic disease, it should be treated as such,” a spokesperson for Novo Nordisk said. An Eli Lilly spokesperson said: “We expect Zepbound to be used as part of an ongoing disease management strategy for adults with obesity, in addition to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity.”

The FDA told Fortune that it regulates the marketing and distribution of prescription drugs, and that companies are responsible for not misleading customers and being truthful in their product marketing, but the agency declined to comment on any specific companies and whether it had investigated or issued any warnings, noting that the FDA “generally does not comment on pending or potential compliance matters.”

Calibrate was one of the first weight-loss companies to enter what has become a saturated space. In 2019, the company was launched from the startup studio ReDesign Health. Calibrate’s founder and first chief executive, Isabelle Kenyon, with the help of Dr. Donna Ryan, one of the leading names in obesity science, and other advisors, fashioned a 12-month “metabolic reset” program, which promises 10% loss of body weight in a year. It costs $199 per month, not including the cost of medications, and features GLP-1 prescriptions and one-on-one biweekly coaching sessions.

While the company has never run any advertising around tapering off weight-loss drugs, in a YouTube video and blog posts, Calibrate describes its one-year program as a way to “reset” customers’ metabolism. We “help people get on the medication, help people change their behavior, help people get off the medication, at a total cost of care that makes sense for treating obesity,” Calibrate’s founder, Kenyon, said on camera in an interview at a health care conference in 2022, describing how Calibrate worked.

A Calibrate spokeswoman asserted that the company didn’t launch with a formal position around tapering off the medications. But two people familiar with the company’s launch said that Calibrate’s go-to-market strategy and guidance to its coaches, from the beginning, was framed around the idea that GLP-1s could be effective when taken temporarily.

“We wanted to make sure that we stayed on message: This was a temporary thing and the goal is to taper off the drugs and [not to] stay on GLP-1s permanently,” says a former Calibrate health coach, who worked with several hundred of the company’s customers during her time at the company, but asked for anonymity in order to discuss her former employer. A person who worked on Calibrate’s initial marketing strategy, who Fortune granted anonymity because they still work in the field and feared retaliation, agreed that was always the message: “Reset your metabolism, do this for a year, and then off you go—skinny and happy.” Kenyon declined to comment on the record.

At the time Calibrate was founded, there was little existing science on when, or whether, patients could keep the weight off after they stopped using GLP-1s—but the preponderance of research that has emerged since then suggests that few can maintain their weight loss once they stop using the drugs. Dr. Kristin Baier, Calibrate’s vice president of clinical development, acknowledged in an interview with Fortune that there was no research indicating these medications could be temporary at the company’s conception.

The former Calibrate health coach suggested another factor in the startup’s strategy: what insurance companies were willing to pay for. Some insurance companies are balking at paying for these expensive drugs long-term, she said, so at Calibrate “their angle is: We are going to utilize the insurance companies to get people where they need to be, and then once the insurance no longer covers it, you don’t really get this expensive medication anymore,” they said. “But that’s okay, because they’re saying that they should still be able to maintain that weight loss. With the caveat that you’ll gain a little bit back but not a huge amount.”

For its part, Calibrate says it has the interests of its patients at heart, and that it’s acknowledging the fact that many of them are not going to stay on weight-loss drugs for life, given supply-chain shortages, insurance coverage limits, medication costs, issues with side effects, or them not wanting to stay on a medication forever.

“Instead of abandoning those individuals, Calibrate provides them with lifestyle and coaching support to help them sustain metabolic health after medication,” a spokesperson said in a prepared statement. “Our program has never been about the medications alone; Calibrate has always aimed to sustainably increase access to holistic metabolic health care. As a company, we believe it’s important to acknowledge that GLP-1 use is not always continuous and create the programs and protocols to support patients across their entire health journey.”

A few years after Calibrate’s launch, the company itself began collecting data on what happens when customers stop taking the medications. This data reportedly paints an upbeat picture about patients maintaining weight loss—but it is not peer-reviewed and was collected from a relatively small sample size of 109 customers over just six and a half months. Calibrate declined to share the complete study with Fortune, but Dr. Baier said 93% of these patients maintained a loss of more than 10% of their body weight for 26 weeks after they stopped using the medication and 82% sustained more than 15%—so long as the tapering was paired with changes in diet, exercise, sleep, and emotional health (the same kind of thing doctors have been recommending for weight loss for decades).

In interviews with Calibrate’s chief executive Rob MacNaughton and Dr. Baier, both cited this internal data as evidence for the company’s model and said that a “material number” or “some people” can get off the medications and maintain weight loss—and Dr. Baier pointed out that the larger studies suggesting that the drugs have to be taken long-term are being funded by the drug manufacturers.

“There is no question that some individuals will do best with ongoing uninterrupted medication support,” Dr. Baier said in a written statement sent later. “But others may be able to maintain results by transitioning to a low-maintenance dose, by spacing out the injection frequency, by transitioning to a different anti-obesity medication, or—as we’ve seen in parallel spaces like diabetes and high blood pressure that also rely heavily on medication—by discontinuing medication altogether while leaning into lifestyle changes.” Calibrate advisor Dr. Ryan said that “we do need better evidence” around whether some individuals can maintain weight loss after coming off GLP-1s, but she thinks what “Calibrate is doing is sharing the decision-making with the patient and trying to adapt to the environment where drugs may not always be available.”

Since Calibrate has come onto the market, results were published from a much larger, peer-reviewed study funded by the Ozempic manufacturer Novo Nordisk in 2022. The study, which was a trial extension and tracked 327 people, showed that the 228 participants who stopped taking semaglutide regained a mean of two-thirds of their prior weight loss within a year. In 2023, a second piece of research sponsored by Eli Lilly (maker of Mounjaro and Zepbound) was published. This study, which reviewed how 783 adults responded when taking tirzepatide for 36 weeks, found that a subgroup of 335 who were taken off the drugs and switched to a placebo for about a year regained an average of 14% of their total body weight, while another group who continued to take GLP-1 medications lost another 5.5%.

Michelle Isherwood, a 54-year-old attorney living in Massachusetts, started using Calibrate after seeing it on her social media feed. She used the platform for approximately six months, taking GLP-1 medications, and had lost about 50 pounds by the time she stopped taking them after a bad reaction. She didn’t think quitting the drugs would be that big of a deal: She had lost as much as she wanted to, and in her mind, the company’s messaging throughout her two years had suggested that, “unless you were a diabetic, there was no need to stay on the GLP-1.” But Isherwood told Fortune that within six to eight months, she gained back about 20 pounds as she reverted to old behaviors when stressors arose in her life—a familiar pattern that she’d experienced before.

“I just wasn’t doing what I was supposed to be doing,” Isherwood said. While taking the drugs, she said, “you’re just not hungry.” But once she stopped taking the medicine, she said, “I have more cravings.” Still, she’s happy with where she’s at now with her weight, after two years of Calibrate’s program.

In anonymous complaints about Calibrate filed with the Federal Trade Commission and obtained via a Freedom of Information Act Request, one patient wrote: “I have regained half of what I originally lost, a setback representing about six months of work.” Another customer said they started gaining weight back as soon as they stopped the medication cold turkey, so they got back on the medication by signing up for Calibrate’s second-year program.

Others who spoke with Fortune, who got drugs directly from their primary care physicians rather than a startup, also said they regained weight shortly after stopping the medication. Claudia Castro, a 31-year-old software engineer, lost about 33 pounds during the first two months she was taking Ozempic. She stopped taking it because she was paying out of pocket and because of a move, and within a couple of months had put back on about 23 pounds—about 70% of the weight she had lost. “Everything that comes fast, goes fast,” she says, noting that she started seeing a nutritionist and working out, and has since been able to start losing the weight again.

“When we stop these medications, especially, the hunger comes back very strongly, so there is a large association between stopping the medication and having that weight regain,” says Dr. Alyssa Dominguez, an endocrinologist at Keck Medicine of USC. There’s also the fact that after weight loss, many people’s metabolisms actually slow down—making it progressively harder to maintain or continue shedding pounds.

An editor for the Wall Street Journal, Bradley Olson, recently detailed his experience after he lost 40 pounds while taking Mounjaro, then stopped taking the medication. He called the four months after going off medication “a roulette wheel of binges, diets, exercise regimens and mental and emotional battles with myself over will power, self-image and motivation.” Olson said he gained back five pounds within two months, but was eventually able to lose it by imposing a strict regime: 12 hours of exercise a week and an extremely high-protein diet.

By the time Noom entered the GLP-1 business in May 2023, both the Eli Lilly– and Novo Nordisk–funded studies, which found that most gain back much of the weight they lost after going off the drugs, had been published.

Still, Noom’s Noom Med program—which costs $49 per month in addition to the price of medications and the standard Noom subscription—would begin marketing GLP-1 medications as temporary. The company’s then chief medical officer, Dr. Linda Anegawa, who has since left the company, said on stage at a health conference in October of 2023 that Noom estimated 80% of its users who were prescribed GLP-1s would be able to “successfully off-ramp,” or wean themselves off the medications. (At the time of publication, Noom had not yet provided Fortune with data to support this.)

Noom has run advertisements on Reddit, Instagram, and Facebook that read “weight loss meds don’t need to be forever,” “Ozempic doesn’t need to be forever,” and “for a majority of patients, GLP-1s are not a ‘forever’ solution.” (Noom declined several requests to make people at the company available for an interview, and Dr. Anegawa did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

In February, Noom’s Dr. Anegawa in a live-streamed event explained in further detail how Noom’s program works—saying once a patient hits their goal while on GLP-1 medications, the “off-ramping process can begin.” Similar to Calibrate, Noom says that changes in diet and exercise will keep weight off. However in that same video, Dr. Anegawa acknowledges that tapering off of medication is “under active study” and there isn’t research available to show when a person can get off a GLP-1 and successfully maintain weight loss. “There really [isn’t] any data out there that specifically link the time spent on GLP-1s on the ability to maintain the weight,” she said.

Noom has run advertisements on Reddit, Instagram, and Facebook that read “weight loss meds don’t need to be forever,” “Ozempic doesn’t need to be forever,” and “for a majority of patients, GLP-1s are not a ‘forever’ solution.”

When asked by Fortune what research supported the temporary usage of GLP-1s, Noom, Calibrate, and Embla all shared the same data points and one another’s internal research. They argued that, as the Noom spokeswoman put it, a “number of studies have demonstrated sustained weight loss post medication removal.”

The research they sent, however, underscores how nascent this particular area still is. One study from earlier this year says more than half of 20,274 patients who lost at least five pounds on semaglutide were “around the same weight” one year after coming off the medication. But the study is not peer-reviewed, and three doctors who spoke with Fortune raised concerns about it being unclear on its methods, inclusion and exclusion criteria, other medications or surgeries that may not be accounted for, and whether participants continued a planned diet and exercise regimen post-medication. Of those three doctors, one said she’d take the study with a “large grain of salt.” Another plainly called it “garbage.”

The companies also pointed to a study showing the importance of exercise in maintaining weight loss, and to data published by one another that has not been peer-reviewed—the Calibrate data on 109 customers, and Embla’s tracking of 85 of its GLP-1 users, who it said had maintained a “stable” body weight for 26 weeks after going off the medication.

In response to a request for comment, Embla’s chief medical officer, Henrik Rindel Gudbergsen, said that “lifestyle changes in combination with weight loss medication seems to allow patients to avoid regaining weight after coming off medication… However, as this is a new area of interest for clinicians and researchers, we cannot make any firm conclusion.”

The seven doctors who spoke with Fortune (most of whom, like Dr. Ryan and many other prominent obesity doctors, have consulted, advised, or worked with the drug manufacturers Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly in some capacity) emphasized that the science is still young. But they said that the bulk of the peer-reviewed research to date shows that few people can maintain all of their weight loss after coming off GLP-1 medications.

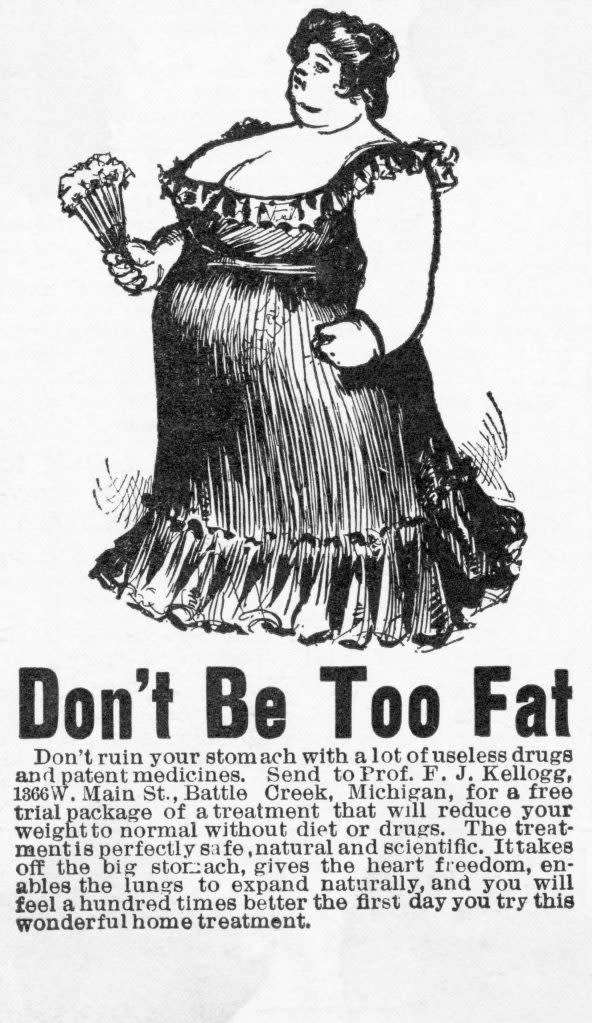

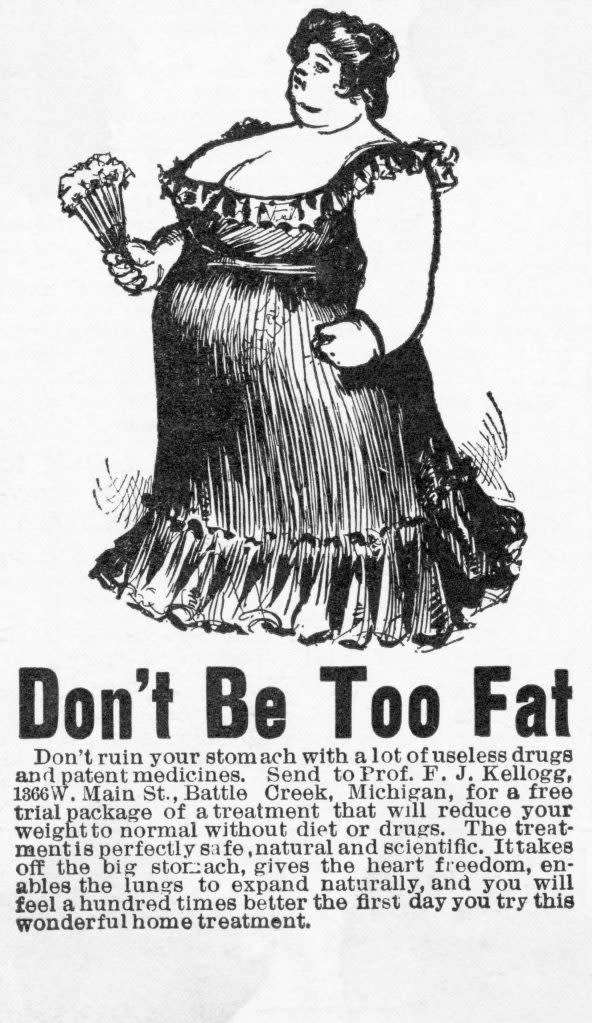

Diet companies making promises that play on customers’ desires, fears, and anxieties is nothing new, of course. As Chastain pointed out, she often sees companies in the weight loss industry promote things that are either not based in science, or not based in enough science. “Stuff that would be rejected at a sixth-grade science fair project gets published and put in marketing,” she said. “It’s pretty ridiculous.”

And it’s worth noting that for some patients, these weight-loss programs that include drugs can be powerful—even life-changing enough that they might be worth committing to long-term. Before becoming a member of Calibrate, Isherwood remembers seeing a number on the scale that she’d never seen before. “It was the highest I’ve ever been,” she said, later adding: “I was freaking out, so I tried going back to kind of eating low-carb and exercising; it just wasn’t working.”

Apart from some hiccups, such as slow responses from the company’s customer service and difficulty reaching doctors or coaches, Isherwood says, her experiences with Calibrate were positive and pleasant, and that’s why she remained a customer for two years. After all, she lost weight.

The solution that both Calibrate and Noom suggest for customers who stop using weight-loss drugs might sound simple, and familiar: diet, exercise, sleep, emotional health. But decades of data show these lifestyle changes are far easier said than done for many Americans—and it’s often because diet and exercise aren’t working for people that they decide to go on GLP-1 medications in the first place.

“We’ve been talking about lifestyle modification and diet and exercise for decades and decades, and we haven’t seen that be really as effective of an intervention as we would have liked, right?” Dr. Matthew Gilbert, a professor of medicine at the University of Vermont, says. “Americans keep continuing to gain weight.”

The desire to lose weight may not just be about health. As Tigress Osborn, executive director of the advocacy organization the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance, explains, it’s “harder to be in the world as a fat person—especially as a very fat person,” she tells Fortune. “The fantasy of just being able to escape all that by losing weight is really powerful. It’s really powerful, and it’s lucrative—and so it’s going to be used over and over and over again to motivate people.”

The promise of a quick fix, via a weight loss program, diet, or drug has made many fortunes. And it’s a history with its share of ignominy: In the mid-1990s, a drug that combined fenfluramine and phentermine, known as fen-phen, exploded in popularity after a single, 121-patient study showed it was effective for weight loss. At its peak, more than 6 million Americans were on it, and doctors centered entire practices around it—until it emerged that it was increasing the incidents of heart valve defects, and the FDA requested it be pulled from the market. The drugmaker eventually agreed to a $3.75 billion settlement, at the time one of the largest ever payouts in a product liability case. The episode was, the New York Times proclaimed, “a morality tale for our times.”

The excitement around GLP-1s feels eerily similar to the fen-phen craze, says Osborn. “If you’re of a certain vintage, and you were in diet culture as a dieter, as a fat person, as a sociologist observing these things…then you might be a little more skeptical of this one,” she says.

To be clear: No evidence has emerged of GLP-1s causing health problems on a large scale (though some studies have linked a few fatalities to hypoglycemia that emerged after using GLP-1s or an increased risk of pancreatitis or bowel obstruction). But in such a new field of research, customers of these weight-loss startups are essentially test subjects, says Chastain: “The danger to consumers is that they take on risk and expensive medication based on a claim that is not scientifically based—that’s not evidence-based.”

Startups, by nature, exist to fix problems. And the GLP-1 industry, with its steep price tags and periodic shortages, has a number of them. But an important question these companies must reckon with is whether it is science or scale that is driving their business strategy, says Dr. Rekha Kumar, the former medical director of the American Board of Obesity Medicine and the chief medical officer at a weight-loss startup, Found (which prescribes GLP-1s sparingly and with the caveat that they are to be taken long-term).

“It’s really important to try to build a healthy business around the right clinical strategy, and not the opposite,” she says. “Not for a company to say: ‘Oh, this is how I know we’re going to make money. So let’s build a clinical strategy around that’… I think that’s a big mistake.”

It remains to be seen how all these startups will fare as more and more patients quit their weight-loss medications. Dr. Peminda Cabandugama, the director of digital obesity at Cleveland Clinic, issued a prediction about those who go to what he called “Instagram clinics” for their weight-loss drugs and fail to pair them with an ongoing regime of diet and exercise—one that could be dire for the industry. “Around 2025,” he told Fortune, “there’s going to be a lot of people regaining their weight.”

And there are some clues that weight-loss companies are starting to prepare for that eventuality: In recent weeks, Noom has released a new round of Instagram advertisements—many of them with the “temporary” language taken out.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com