El Niño and La Niña are two extremes that have far-reaching effects on our weather here in Canada and around the world.

These spells of abnormally warm and cool waters in the eastern Pacific Ocean are chief players in driving our seasonal weather patterns.

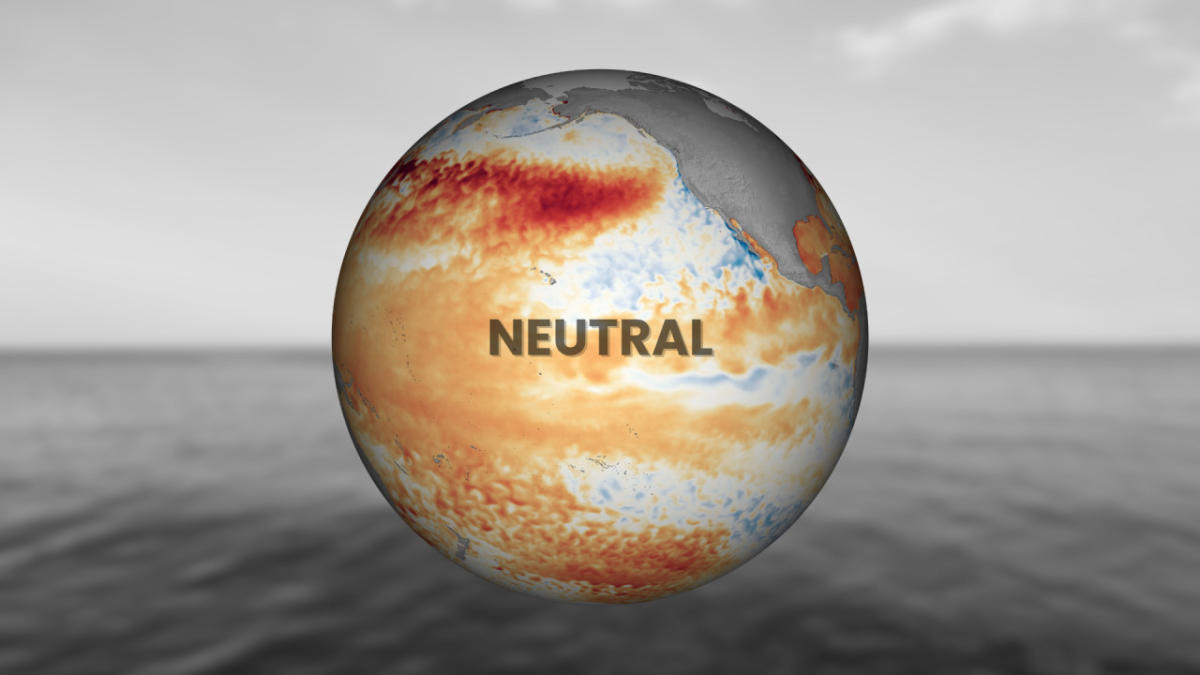

But what happens when neither pattern is present? These periods between extremes are known as a “neutral” phase.

Check out The Weather Network’s hub page for all the latest on El Niño, La Niña, and what it means for your seasons ahead!

It’s sometimes hard to imagine that water temperatures in a relatively small patch of the eastern Pacific off the coast of South America have such a tremendous effect on global weather patterns.

Water temperatures coming in at least 0.5°C warmer-than-normal for about seven consecutive months makes for an El Niño event, while the same waters reading at least 0.5°C colder-than-normal for the same amount of time counts as a La Niña event.

DON’T MISS: What is La Niña? And how does it impact global weather?

El Niño can have a profound effect on winters across North America, generally bringing warmer conditions to Western Canada, a chilly pattern for the Great Lakes, and very wet and stormy weather for snowbirds heading south to Florida.

La Niña, on the other hand, leads to cooler winters out west while a volatile pattern sets up across Eastern Canada. During the summer months, La Niña can make conditions more favourable for hurricanes to develop in the Atlantic Ocean.

These patterns are all tied to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which is the pattern of prevailing winds that pushes and pulls on surface waters across the Pacific Ocean.

The extremes of El Niño and La Niña aren’t always present. Meteorologists consider these interim periods to be “ENSO-Neutral.”

MUST SEE: El Niño and wind shear: Atlantic hurricane season influencers

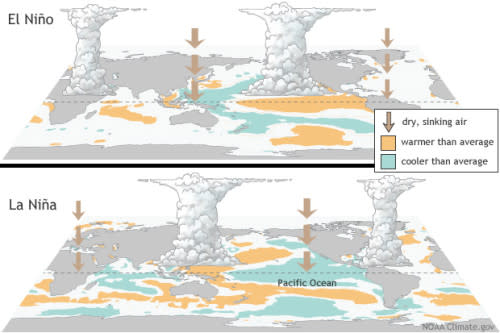

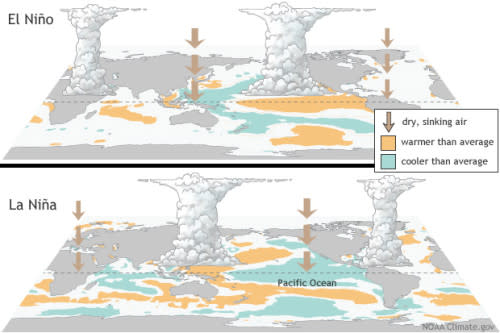

A diagram of the patterns that create El Niño and La Niña over the Pacific Ocean. (NOAA)

During normal conditions, prevailing winds blow from east to west, pushing surface water from South America toward Australia. This allows warm water to drift west while cold water from deep within the ocean rises off the coast of Peru and Ecuador.

El Niño forms when those winds break down or even reverse direction, sending that warm water surging back east toward South America. La Niña develops when those winds strengthen, accelerating the process that forces cold water to rise to the surface near South America.

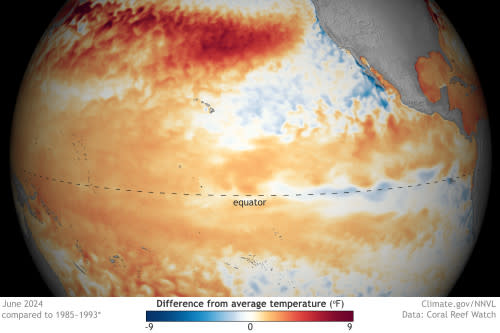

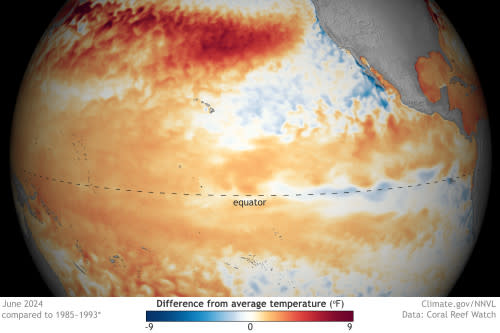

A map of ENSO-Neutral conditions across the Pacific in June 2024. (NOAA)

Periods when water temperatures are within 0.5°C of normal are referred to as neutral. It’s very rare that water temperatures are bang-on seasonal for that time of year—they’re always slightly above or below normal.

But the temperature anomalies present during neutral phases aren’t great enough to affect the global weather patterns in a meaningful way. Weather patterns during ENSO-Neutral conditions are often pretty close to normal for that particular season.

However, La Niña and El Niño can start to develop during neutral periods.

If water temperature anomalies climb higher than that all-important one-half degree threshold, we can begin to see increasing effects on wintertime temperatures and Atlantic hurricane activity—even if we’re not officially in an El Niño or La Niña pattern.

Header graphic created using imagery from Canva and NOAA.