Panenka – the penalty that killed a career and started a feud

In the end, the Germans’ eagerness to get to their sun loungers changed history.

Their Euro 1976 final against Czechoslovakia was never meant to go to penalties.

West Germany – defending European champions, reigning World Cup winners – were heavy favourites.

Even if Czechoslovakia held out through extra time, the initial plan had been for a replay two days later. Welsh referee Clive Thomas had been told to delay his return home from host nation Yugoslavia to cover the eventuality.

A few hours before the match though, the plan changed.

“It was a request from the German Football Association,” remembers Antonin Panenka.

“They said that their players had already booked some holidays, blah, blah, blah, and asked if penalties could be taken straight away instead of a replay.”

Czechoslovakia figured, as underdogs, they were more likely to prevail in a shoot-out than a second match, so they agreed.

Panenka, an elegant, passing playmaker, mentally checked his plan once more.

All was in order. No alteration necessary, no doubt admitted.

A ploy two years in the making that would make him famous and infamous, a hero and an enemy – whether it succeeded or not – was ready.

Back home, Panenka had been involved in another, almost daily, penalty contest.

After training at his Prague club side Bohemians, Panenka and goalkeeper Zdenek Hruska would stay behind to practise spot-kicks.

It was a very personal duel. Panenka would have five penalties – he would have to score all five, Hruska would have to save just one. Whoever lost would buy their post-training beer or chocolate.

“I was constantly paying him,” says Panenka.

“So in the evenings I would think up ways to beat him – that’s when I realised that as I ran up the goalkeeper would wait for the last second and then gamble, diving to the left or the right.

“I thought: ‘What if I send the ball almost directly into the centre of the goal?'”

Panenka tried it. He found that introducing another possible penalty and some hesitation to Hruska’s mind meant he was winning more, spending less and still getting his post-training treat.

It could have stopped there and remained a piece of unseen showboating. But Panenka realised his new technique was more than that. He had unearthed a legitimate 12-yard tactic.

Over the next couple of years, he tested it on larger and larger stages. First, in training, then in friendlies and finally, the month before Euro 1976, against local rivals Dukla Prague in a competitive fixture.

Each time it worked and his conviction grew.

“I made no secret of it,” Panenka says.

“Here [in Czechoslovakia] people were well aware of it.

“But in western countries, in top football countries nobody was interested in Czechoslovak football at all.

“Maybe they were kept up with some results, but they didn’t watch our games.”

So, there was no laminated cheat sheet or whispered instructions from a backroom analyst for Sepp Maier.

As the West German goalkeeper crouched on his goalline and fixed his eyes on Panenka, he had only his own instincts to go on.

Maier’s team-mate Uli Hoeness had blazed the previous spot-kick over the bar. It was the first miss of the shoot-out, after extra time finished with the teams still locked together at 2-2.

Instantly the stakes became sudden death and sky high. If Panenka scored, West Germany were beaten.

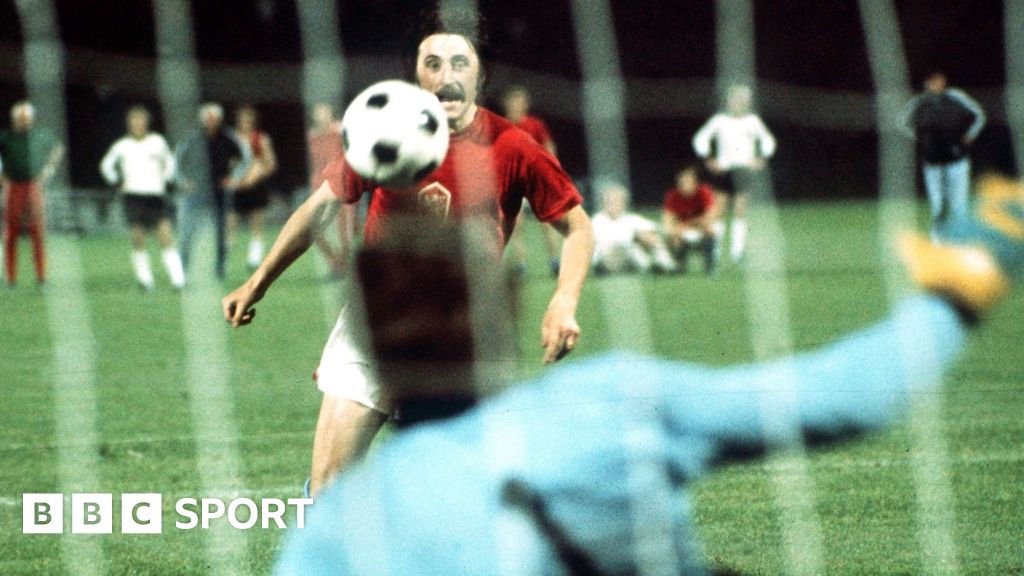

Panenka’s run-up was long and fast. He seemed intent, like Hoeness, on thumping his instep through the back of the ball.

Instead, with the most important kick of his life, he fell back on his trusted trick. A deft tickle sent the ball floating down the centre of the goal. Panenka’s arm was aloft in celebration before it hit the net. Maier, flummoxed and failing, scrambled back to his feet, but only in time to shoot a rueful look at Panenka wheeling away in celebration.

“None of us could believe we were European champions,” said Panenka. “It was like Alice in Wonderland.”

It was just as surreal back in Prague. Their European Championship win came eight years after the Prague Spring – when a Soviet-led herd of tanks had rolled across the border and crushed attempts to loosen the country’s communist system.

Since then, large public gatherings had been rare, permitted only for orchestrated welcomes of foreign dignitaries. When the team arrived with Czechoslovakia though, there was no holding back the emotion or the numbers.

“Nobody expected that so many people would come to give us such a warm welcome,” Panenka remembers.

“When some head of state came, the roads used to be lined with young people holding parade wands.

“But it was all sort of forced. This time though they all came spontaneously to greet us and show their appreciation. I had never experienced anything like that before. It was one of the best moments of my football career.”

Panenka’s decisive, distinctive penalty made him centre of attention. Not just for the crowd, but for the authorities as well.

Czechoslovakians had been subjected to a process dubbed ‘normalisation’ since their attempt to diverge from the Soviet model. The remoulding or removing of dissident elements had gone far beyond politics.

Just three months before Euro 1976, Czechoslovakia’s secret police had arrested a psychedelic rock band and other underground musicians, fearful that long hair and counter-cultural lyrics alone could fuel revolution.

Panenka’s penalty – hit with a disregard for convention and causal panache – was definitely not “normal”.

To repeat his trick on a stage of such scale carried significant personal, as well as sporting, risk.

“I would never have thought that politics and sport or politics and football could be linked like this, but it’s true that there were some looking at it in this way,” says Panenka.

“When it was discussed in political circles, they could take it as my contempt for the political system.

“If I hadn’t converted the penalty, it probably would have had some consequences for me, some sanction or another problem.”

That Panenka found the net spared him uncomfortable questions and a possible new career in a factory or mine.

But by scoring he made another enemy.

Defeat was an unusual sensation for Maier, part of a Bayern side that had won it’s third straight European Cup the previous month. Humiliation was unheard of.

The Scotsman’s report from Belgrade described how Panenka’s one kick blew apart two preconceptions: Czechoslovakia’s faceless, collective style and West Germany, and Maier’s, inevitable competence, control and victory.

“Czechoslovakia’s old, hard discipline is still evident,” wrote Ian Wood.

“But the cult of the personality has gained more than a fragile toe-hold and nowhere was the new zest more perfectly illustrated than when Panenka gave the Czechs the championship by grounding the hapless Sepp Maier with a dummy of supreme impudence.”

Elsewhere there were harsher descriptions than “hapless”.

“Some foreign journalists, especially the ones from the West, insisted that I made fun of Maier, that I made him a clown and things like that,” says Panenka.

“It was not true. For me, it was just the easiest way to score a goal. But Maier believed what those journalists wrote about me having ridiculed him.

“Whenever he heard the name ‘Panenka’, it was terribly unpleasant for him and he would react very irritably.

“He didn’t speak to me for the next 35 years.”

Image source, CTK/Krumphanzl Michal

But as the decades passed, there has been a thaw.

Since the original, the ‘Panenka’ has been repeated and proven as a bona-fide – if high-risk – tactic by some of the biggest names on the most momentous occasions.

Zinedine Zidane scored one in the 2006 World Cup final against Italy. Memorably for England fans, Andrea Pirlo clipped one past Joe Hart in a Euro 2012 shoot-out. Lionel Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo, Thierry Henry, Neymar and Zlatan Ibrahimovic have all pulled it off.

Maier is no longer a lonely fall guy. Plenty of goalkeepers have been similarly beaten. The sting of 1976 has been drawn, the stigma is gone. Mostly.

Maier declined a request to be interviewed for this article.

“I think that our relationship has been perfectly normal lately,” says Panenka.

“The last time I met him was four or five years ago. There was some press conference arranged by the German side here in Prague, and I could see that he wasn’t annoyed or angry with me. We had a beer and played golf together.

“He could even smile about the penalty kick. When he first saw me on that most recent trip, he wagged his finger at me and gestured the trajectory of a chipped ball with his hand.”

Even Panenka’s own relationship with his 1976 penalty is complex.

His fizzing set-pieces, his dead-eyed shooting, his scalpel-sharp passing goes uncredited, buried under the fame of his own creation.

“I am a bit down the middle about it,” he says fittingly and finally about the 1976 penalty.

“On the one hand I am proud that the penalty was invented, that it is so famous and that it is repeated by the best players. But it’s true that whenever the name Panenka is mentioned, everybody just thinks about ‘the Panenka penalty’.

“So on the one hand I am proud, but on the other hand I am a bit unhappy that the penalty erased everything I wanted to give the viewers – a lot of passes, goals, chances I created.

“In a sense, the penalty killed my career.”

If he had that moment again, staring down Maier, the European Championship on the line, would he dare to do the same again? Or would he play it straight with a shot that wouldn’t define him forever for so many?

Panenka’s answer is emphatic.

“Of course, I would do the same! Sure! I can’t do anything else.”