Getty Images

Getty ImagesCanada is searching for an international grocer to enter its domestic market, after years of anger from shoppers over high food prices, much of it directed at one of the big players. But would an Aldi or a Lidl solve the problem?

Late last year, Emily Johnson took to Reddit to share her frustration with how expensive food in Canada has become.

She fixated on one grocer in particular: Loblaw, the dominant food retailer in Canada, boasting nearly 2,500 stores.

Her Reddit group – named LoblawsIsOutofControl – was filled with photos of grocery items for sale at seemingly egregious prices, like C$40 ($29.36; £23.06) for 1.4 kilograms of chicken.

Soon after, Ms Johnson and others banded together to launch a nation-wide boycott against Loblaw, saying they were fed up with the disparity between rising food prices and record profits.

The company, which also operates pharmacy and discount grocery stores, made a profit of C$2.5bn in 2023 – a nearly 10% increase from a year earlier.

As anger grew, the grocer’s former president Galen Weston, who has defended the profits, became the de facto face of food inflation in Canada, thanks to his regular appearances in Loblaw commercials and his annual reported salary of C$8.4m.

Some even began selling T-shirts featuring a spoof “Roblaw$” logo, which were met with copyright infringement complaints from the grocer.

The boycott, which began in May and is set to continue indefinitely, has since sparked a national conversation on how groceries in Canada are priced, and why a company like Loblaw continues to be profitable as more Canadians struggle to afford food.

It has also ignited political pressure and scrutiny on the grocery practices of not just Loblaw, but other major grocers in the country.

“Groceries did not used to be such an issue but the prices have skyrocketed this past year so we’re going without anything frivolous,” Terra Suffel, a 49-year-old single mother of two living in Toronto, told the BBC.

President’s Choice/YouTube

President’s Choice/YouTubeA C$200 shopping spree used to feed Ms Stuffel and her children for the entire week, she said. Now it barely covers lunch ingredients and much-needed pantry items.

“We can’t really afford much meat and our main protein is now eggs,” she said, adding that she, too, is boycotting Loblaw.

In response to frustrated Canadians like her, Canada’s federal innovation minister has since taken several overseas trips to woo an international grocer to set up shop in Canada, in an attempt to increase competition and therefore drive down food prices.

But experts say that any foreign grocer looking to enter Canada’s market faces an uphill battle to distinguish itself from existing players, and that the country’s unaffordability crisis may require a more complex fix.

Loblaw has responded to the boycott by saying they remain committed to be the “retailer of choice” for Canadians.

In a statement to the BBC, the company added that it was doing what it could to fight inflation and plans on opening more discount stores to make affordable food more accessible.

Like many other countries, Canadians saw the cost of living go up after the Covid-19 pandemic thanks to supply-chain issues and labour shortages.

Although food inflation in Canada peaked at a lower mark, 11.4%, than in the UK and US, according to data by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the overall figure does not tell the whole story.

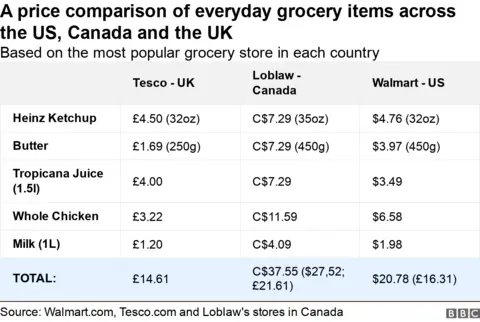

A price comparison between the three countries of some everyday items suggests Canada is indeed more expensive for some of those regular shopping basket contents.

Canadians are also grappling with a currency that is plummeting in value compared to the US dollar, which has impacted both the price of food imported from the US, as well as Canadians’ overall purchasing power.

Rising interest rates, coupled with higher rent and home prices, have also pinched the wallets of many in Canada.

“People are feeling (the rising cost of food) because they are also feeling the rise of mortgage payments and other things,” said Jordan LeBel, a marketing professor with expertise in the food industry at Concordia University in Montreal.

Another issue is the heavily consolidated nature of Canada’s grocery market, said Prof LeBel.

The country’s industry is dominated by three large companies: Loblaw (which operates Loblaw’s stores), Empire (which operates Sobeys stores) and Metro.

They make up nearly 60% of the grocery market share while Walmart and Costco make up much of the rest.

In comparison, the US grocery market features more regional players. And while Walmart is by far the most popular chain across the country, there are more than a dozen other grocers meaningfully competing with it.

Similarly, the UK’s market is also diverse, with a total of 14 businesses turning over more than £1bn in groceries sales per year.

Prof LeBel said the Loblaw boycott is a signal from Canadians who are fed-up with the lack of choice and the country’s grocery behemoths, who lack an incentive to meaningfully tackle rising food costs.

Francois-Philippe Champagne, Canada’s minister of innovation, science and industry, has been tight-lipped on which international grocers he has been trying to court.

But government documents obtained by the Wall Street Journal in April have named 12 potential stores, including Germany’s Aldi and Lidl, France’s Les Mousquetaires, and other companies from Turkey, Spain and Portugal.

Discount supermarket chain Aldi already has nearly 2,400 stores in the US. It is also the UK’s fourth largest supermarket.

Its chief competitor Lidl has a footprint in the UK and the US as well, though a smaller one than Aldi.

Despite their popularity in other countries, retail experts say entering the Canadian market comes with its own unique set of challenges.

“The classic mistake all foreign retailers make when coming to Canada is that they think it is the 51st US state,” said Amarinder Singh, a senior director at consulting firm Kantar.

In reality, Canadian shoppers are very different, he said.

Their needs vary regionally, he said, whether they live in Atlantic Canada or in British Columbia, or whether they call a major metropolitan city like Toronto home.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCanada is also a highly multicultural country with 20% born elsewhere and a national grocer must target them to find success, Mr Singh said.

Another factor to consider is that Loblaw’s strong loyalty points programme covers 40% of Canada’s entire population.

“The issue is how you engage the shoppers, and how you steal the share from the Loblaws and Sobeys and Metros of the world, who have such a strong grasp on this market,” said Mr Singh.

Some have said the minister’s international tour is a bit of political theatre ahead of a consequential election for Canadians where the ruling Liberal Party is significantly lagging in the polls.

“Going after a big player, you have meetings, photo ops – it looks like you’re doing something,” Prof LeBel said.

A spokesperson Canada’s department of Innovation, Science and Economic Development, Riyadh Nazerally, confirmed to the BBC that Minister Champagne has spoken to foreign retailers about “possible investments in Canada”, but no further details.

Canada is working on other measures, like reforming its Competition Act to make it more friendly to new entrants, he added.

Prof LeBel said he believes the government should also focus on building up already-existing regional players and small, local grocers.

Experts have said that the impact of the boycott on Loblaw is likely limited. Local, independent grocers around the country, however, appear to be benefiting, with some seeing a significant boost in traffic and sales since the beginning of May.

Supporting local players, Prof LeBel said, goes a long way in building the local economy and the fabric of a community, while improving competition in the market.