University of New Brunswick isn’t just calling its mini-satellite anymore. The team located in Fredericton has taken to yelling at Violet as the window to reach it closes.

Violet is the first satellite built and designed in New Brunswick to enter the Earth’s orbit. More than 300 people from the province worked on it over five years under the Canadian Space Agency’s CubeSat program.

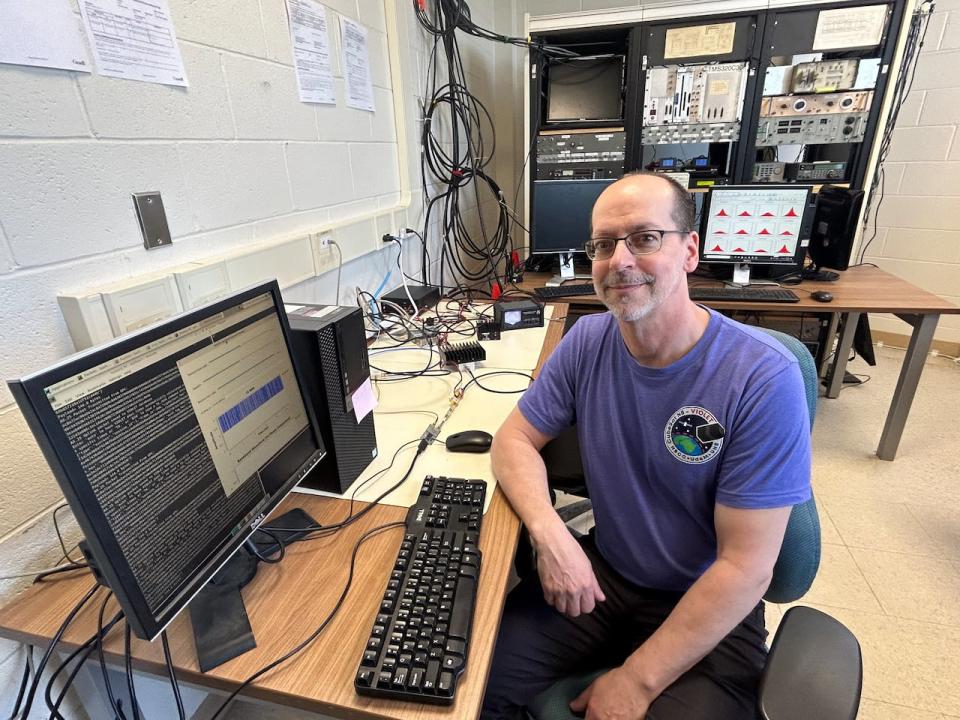

Troy Lavigne, the satellite’s project officer, has been trying to establish contact with Violet ever since it began circling the Earth in April.

He said he has sent more than half a million transmissions, but Violet hasn’t replied.

He said the team started with about 25 watts of power going into the antennas, but that went up to 135 watts once permission was obtained to do so.

“So we began to yell a lot louder,” he said.

Lavigne has also changed the duration and encryption of his commands. He said now he is transmitting longer commands, suspecting the satellite needs more time to pick them up.

He said he also checked the ground station software for bugs and found none.

Troy Lavigne tried multiple attempts to contact the satellite. (Rhythm Rathi/CBC)

Lavigne said in an interview Saturday that the window to reach Violet is very small before it re-enters Earth’s atmosphere. Violet could be lost forever in as little as a few days.

It will burn to ashes upon re-entry. Lavigne said he knows there is a very slim chance to hear back, but giving up is not an option.

“There’s no question that we all feel a tremendous sense of responsibility,” he said.

“We wouldn’t be here today without the hundreds of young future engineers, computer scientists, geoscientists, physicists, who have had their hand in developing Violet, so it will be a total disservice to them to to to give up and say, well, we’re not going to try anymore.”

Unsure but optimistic

Violet was launched into Earth’s orbit from the International Space Station, along with two other mini-satellites.

The Canadian Space Agency confirmed in an email to CBC on Friday that two out of the three satellites have already disintegrated. However, it could not be determined if Violet was one of them, since none of the three communicated with their teams on Earth.

The ground station is connected to an antenna on the roof of UNB’s Gillin Hall. (Aniekan Etuhube/CBC)

“We cannot definitively confirm whether VIOLET was one of the two satellites that completed re-entry,” wrote CSA Spokesperson Maxime Vézina Laprise in the email.

The space agency said the satellites were left without power for 30 minutes until they maintained a safe distance from the space station.

A combination of this delay along with potential failures of parts in the power system, antenna deployment, transponder or onboard computer hang-ups, can all cause a no-contact situation, said the email.

“Without telemetry data, it’s impossible to pinpoint the exact cause or time of failure,” wrote Vézina Laprise.

Lavigne said his team is recording all the data that comes from that last-standing satellite’s frequency, which will later help them study if Violet was sending weak signals that the team could not interpret.

The antenna is designed to oscillate back and forth and side-to-side. (Rhythm Rathi/CBC)

He said even after Violet dies, the ground station has approval to continue communication with other space satellites to teach space-related courses at UNB.