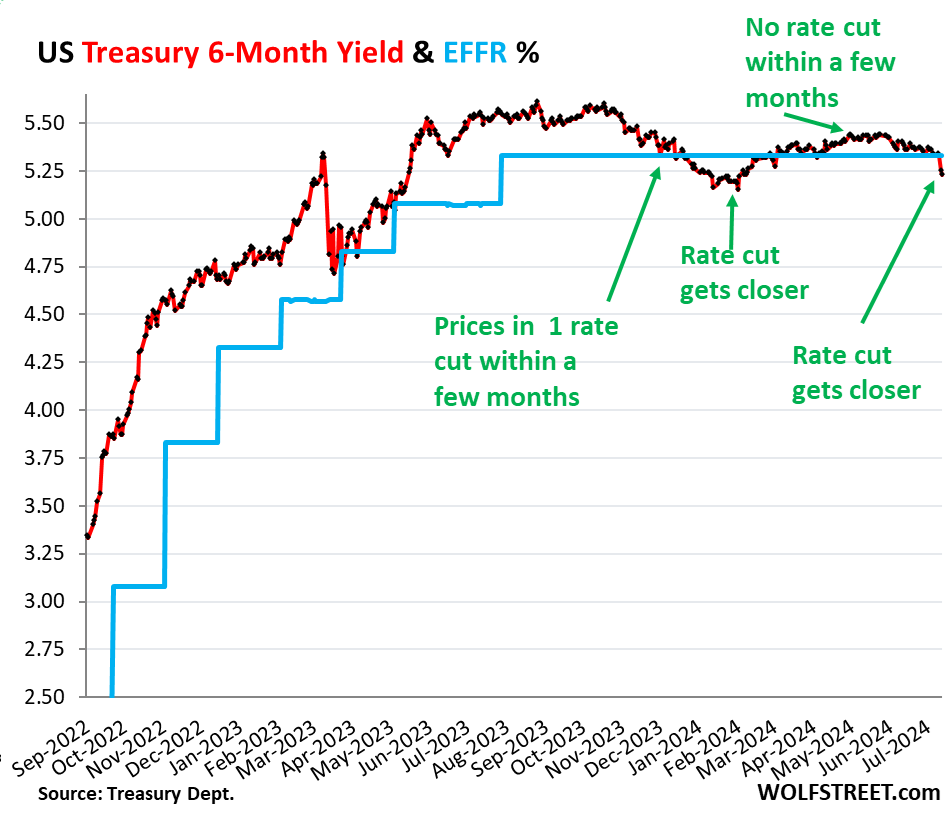

On Thursday, when the CPI report was released with a month-to-month reading of -0.056% (rounded to -0.1%), the six-month Treasury yield dropped by 8 basis points, and on Friday by another 2 basis points, to 5.23%. That combined 10-basis-point drop was a significant and visible 2-day move.

It brought the 6-month yield just a tad below the lower end of the Fed’s target range for the federal funds rate (5.25-5.50%), and below the effective federal funds rate (EFFR), currently 5.33% (blue in the chart below):

So the 6-month yield is now pricing in one rate cut within its 6-month window, more heavily weighted toward the first two-thirds or so of that window, after having already wrongly done so at the beginning of this year.

Back in late November through January, the 6-month yield had also priced in a rate cut within its 6-month window. By February 1, the yield had dropped to 5.15%, a sign the market was certain that there would be a rate cut at the March FOMC meeting.

But the market was wrong. Instead, we got a series of ugly inflation readings for January, February, March, and April, and there still hasn’t been a rate cut.

By March and April, with ugly inflation readings accumulating, rate cuts within the 6-month window of the 6-month yield were taken off the table.

May had provided a much softer inflation reading. And with Thursday’s CPI report of June, a rate cut within the 6-month window of the 6-month yield, weighted toward the first two-thirds of the window, was back on the table.

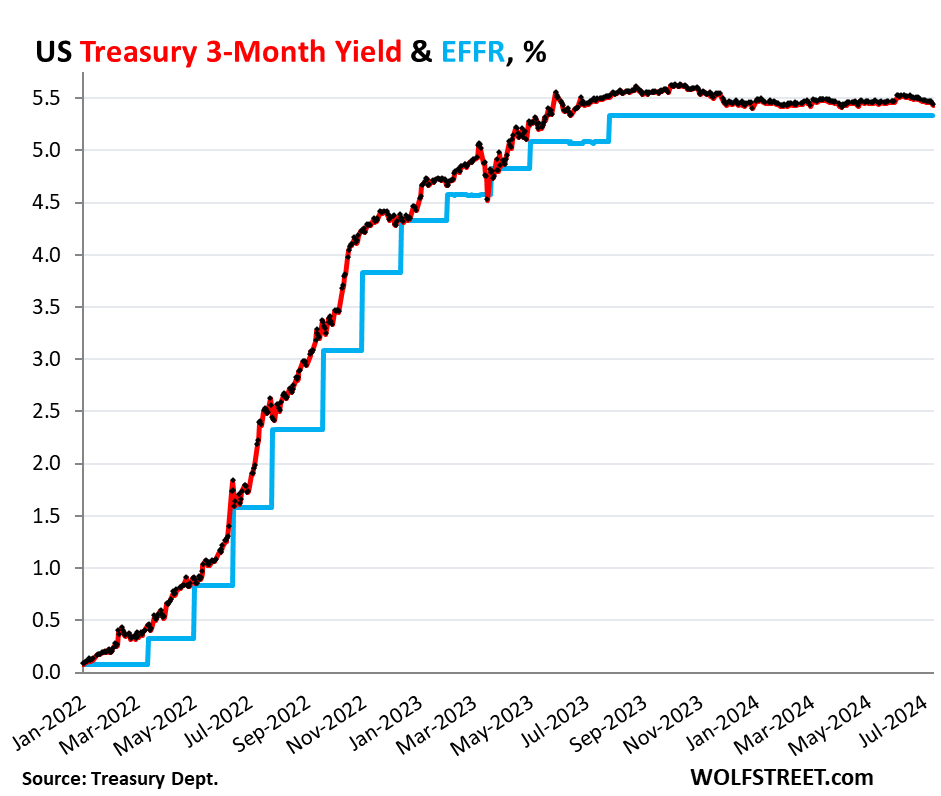

But the shorter-term Treasury yields are not pricing in a rate cut within their shorter windows. The shorter yields didn’t move much since the CPI report, and all were near the upper end of the Fed’s policy rates (5.5%), and all were above the EFFR (5.33%):

In other words, the Treasury market is not expecting a rate cut in July at all, but sees a good chance of a rate cut in September, not as strong a chance as they saw in late January, when they saw a rate cut with near certainty by March that never came.

The three-month yield is not seeing any rate cuts within the first two-thirds of its window. No rate cut in July, and the September 18 FOMC meeting statement is beyond the first two-thirds of the window and has less impact on the current three-month yield:

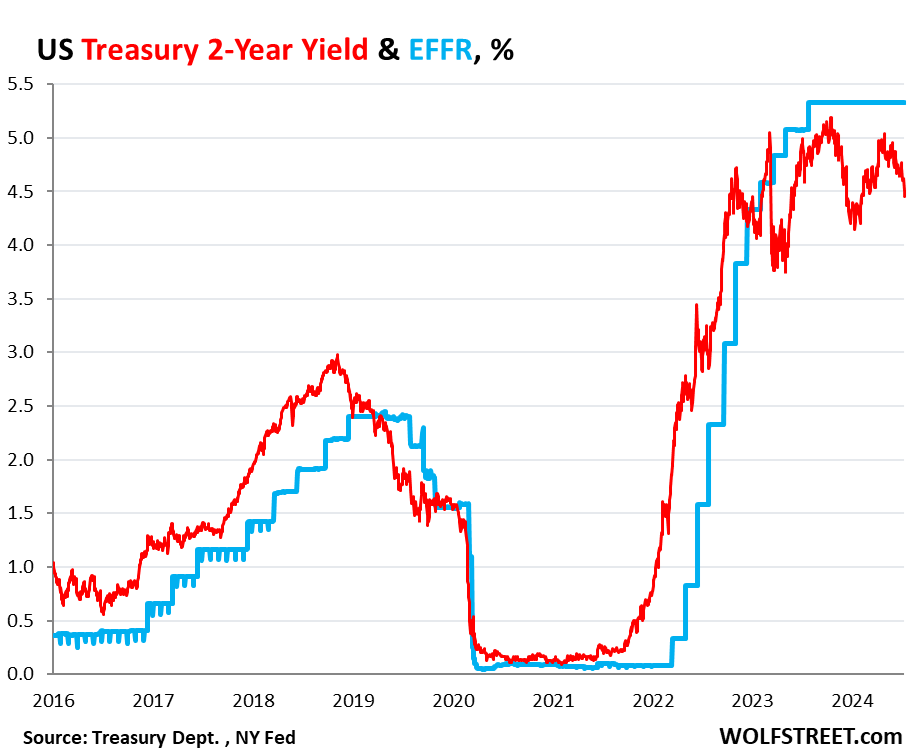

The 2-year Treasury yield demonstrates how wrong the Treasury market has been all along about the Fed’s rate hikes and rate cuts: it expected far fewer and smaller rate hikes than what the Fed eventually did. And then without ever rising to the level that would price in the actual rates that the Fed has held for nearly a year, it started pricing in rate cuts before the Fed even stopped hiking rates.

So back in April 2022, the two-year yield was about 2.5%. Now, today, 2.5% sounds like a lousy yield, but back then – after 15 years of 0% interrupted by a few years of higher yields that maxed out at around 2.4% in 2019 – 2.5% sounded pretty good, and the market thought that was getting pretty close to the Fed’s terminal rate.

In February 2022, before the Fed’s rate hikes started, Goldman Sachs predicted that the Fed would hike seven times in 2022, each by 25 basis points, and then in 2023 three times by 25 basis points each, one hike per quarter, to reach a terminal target range for the federal funds rate of 2.5-2.75% by Q3 2023.

The Fed ended up doing more double that, and by July 2023.

So the 2-year Treasury note that sold at auction in April 2022 with a coupon of 2.5% and with a yield close to that sounded like a good deal, and we, being part of the Treasury market, nibbled on some too. Two years was as long as we went. The rest of our Treasuries are T-bills.

Those 2-year notes matured in April 2024, and we got paid face value, and we earned about 2.5% in interest each year over those two years. The entire market was wrong – and so were we. The Fed would raise to 5.25-5.5% by July 2023, more than double the yield we received, and its rate is still there, and the yields of our two- three- and four-month T-bills have by far outrun our 2-year note.

The 2-year yield closed at 4.45% on Friday. The market never once came even close to betting that the Fed would hold rates above 5% for long, and they’ve been above 5% for over 14 months. And the 2-year yield has been below the EFFR for almost the entire time since January 2023, having turned into the Doubting Thomas.

The market was wrong about the Fed’s rates, and all 2-year notes that were bought at auction and that matured in 2024 or will mature in 2024 were a lousy deal. Buyers would have been better off with a series of short-term T-bills that stick close to Fed’s actual policy rate — rather than follow market projections.

Someday, the market is going to get the rate-cut bets right. But it will only take a few more lousy inflation readings for the rate cuts to get moved further into the future. On Friday, the PPI showed up with red-hot services inflation, now delineating a clear U-Turn in December. Producers that pay those higher prices for services will try to pass them on, and so they may ultimately filter into consumer prices and higher inflation readings over the next few months. Or if producers cannot pass on the higher costs of services, their margins will get squeezed.

Inflation is unpredictable. Once inflation has broken out in a big way, as history shows us, it tends to come in waves and tends to dish up nasty surprises. And it already has dished up nasty surprises multiple times so far, including each of the first four months of this year.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()